Wood braved the crowds of yuppies at the annual Design Within Reach blowout warehouse scratch-n-dent extravaganza in Union City this weekend, and all she got me was this totally awesome shark toy designed by Alexander Calder for a third of its normal price: Nothing I could write about Calder could justify the reverence I have for his artistic work; growing up I learned quickly to associate his name with those vibrant stabiles that bring so much life to public plazas, particularly La Grande Vitesse in the Grand Rapids, Michigan plaza that bears Calder's name, as well as the giant red Flamingo stabile that sits within Mies van der Rohe's federal plaza in Chicago, and Calder's Bent Propeller that was virtually destroyed in the plaza outside the World Trade Center on 9/11. And then there are his mobiles. The man invented the mobile. That means every nurseling for the last fifty years who has stared up at rotating, bobbing shapes above his crib has Calder to thank for the hours of entertainment. Sartre, in an essay on Calder, wrote that "a mobile is a little private celebration, an object defined by its movement and having no other existence. It is a flower that fades when it ceases to move, a 'pure play of movement' in the sense that we speak of a pure play of light."

Nothing I could write about Calder could justify the reverence I have for his artistic work; growing up I learned quickly to associate his name with those vibrant stabiles that bring so much life to public plazas, particularly La Grande Vitesse in the Grand Rapids, Michigan plaza that bears Calder's name, as well as the giant red Flamingo stabile that sits within Mies van der Rohe's federal plaza in Chicago, and Calder's Bent Propeller that was virtually destroyed in the plaza outside the World Trade Center on 9/11. And then there are his mobiles. The man invented the mobile. That means every nurseling for the last fifty years who has stared up at rotating, bobbing shapes above his crib has Calder to thank for the hours of entertainment. Sartre, in an essay on Calder, wrote that "a mobile is a little private celebration, an object defined by its movement and having no other existence. It is a flower that fades when it ceases to move, a 'pure play of movement' in the sense that we speak of a pure play of light."

Only recently did I learn that Calder began his artistic career by designing toys. In 1927 he designed a series of kinetic toys for the Gould Manufacturing Company of Oshkosh, Wisconsin that in their design bear witness to Calder's mechanical and artistic genius. Most of the toys are pulled by a string, and lurch along in various movements that mimic the movements of the creatures they were designed to represent: a frog, a seal, a skating bear, a kangaroo, a cow, a shark. Calder designed them to be pulled on axles that connected the wheels not at their center but at what are called "eccentric" points. Thus, the frog and the kangaroo hop. The duck bobs like real ducks do. And the shark lurches on its wheels, allowing its tail to shift back and forth like a fish navigating currents. Before embarking on his toymaking career, Calder graduated from the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey, with a degree in mechanical engineering. One can't help but speculate that this early application of engineering principles to a few deceptively simple toys ultimately led to his intricately balanced and wonderfully playful mobiles.

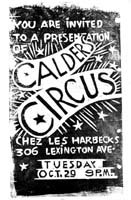

Only recently did I learn that Calder began his artistic career by designing toys. In 1927 he designed a series of kinetic toys for the Gould Manufacturing Company of Oshkosh, Wisconsin that in their design bear witness to Calder's mechanical and artistic genius. Most of the toys are pulled by a string, and lurch along in various movements that mimic the movements of the creatures they were designed to represent: a frog, a seal, a skating bear, a kangaroo, a cow, a shark. Calder designed them to be pulled on axles that connected the wheels not at their center but at what are called "eccentric" points. Thus, the frog and the kangaroo hop. The duck bobs like real ducks do. And the shark lurches on its wheels, allowing its tail to shift back and forth like a fish navigating currents. Before embarking on his toymaking career, Calder graduated from the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey, with a degree in mechanical engineering. One can't help but speculate that this early application of engineering principles to a few deceptively simple toys ultimately led to his intricately balanced and wonderfully playful mobiles. But there is a clear transition, and it is wonderful to behold: Calder's experimenting with various toy designs led to the development of a complex miniature circus in his studio. Calder had long been fascinated by the circus, and in his twenties he paid his way through art classes by selling a number of illustrations of the Barnum and Bailey's Circus to the National Police Gazette. In the late 1920s, Calder developed his own one-man circus, with tiny performers made of "cork, wire, wood, yarn, paper, string, and cloth," carefully engineered to walk tightropes, dance, tame lions, lift weights, and engage in gymnastics and acrobatics in and above the ring. Acting as omniscient ringmaster, Calder would manipulate the wire performers while his wife wound circus music on the gramophone in the background. While struggling as a more traditional artist in Paris, Calder began two-hour improvised performances of his Cirque Calder that recreated the performance of an actual circus. The show soon became a popular diversion among the Parisian avant-garde, and Calder began charging an entrance fee to see the big-top circus that could be packed into a suitcase. I like to imagine Calder's rented Montmartre studio on some smoky conglomerated pre-War Parisian night, filled with the likes of Jean Cocteau, Picasso, Joan Miro, James Joyce, Fernand Leger, Le Corbusier, Thomas Wolfe, and Andre Kertesz watching the young American perform his wire circus.

But there is a clear transition, and it is wonderful to behold: Calder's experimenting with various toy designs led to the development of a complex miniature circus in his studio. Calder had long been fascinated by the circus, and in his twenties he paid his way through art classes by selling a number of illustrations of the Barnum and Bailey's Circus to the National Police Gazette. In the late 1920s, Calder developed his own one-man circus, with tiny performers made of "cork, wire, wood, yarn, paper, string, and cloth," carefully engineered to walk tightropes, dance, tame lions, lift weights, and engage in gymnastics and acrobatics in and above the ring. Acting as omniscient ringmaster, Calder would manipulate the wire performers while his wife wound circus music on the gramophone in the background. While struggling as a more traditional artist in Paris, Calder began two-hour improvised performances of his Cirque Calder that recreated the performance of an actual circus. The show soon became a popular diversion among the Parisian avant-garde, and Calder began charging an entrance fee to see the big-top circus that could be packed into a suitcase. I like to imagine Calder's rented Montmartre studio on some smoky conglomerated pre-War Parisian night, filled with the likes of Jean Cocteau, Picasso, Joan Miro, James Joyce, Fernand Leger, Le Corbusier, Thomas Wolfe, and Andre Kertesz watching the young American perform his wire circus.

As his reputation among the avant-garde grew, Dutch painter Piet Mondrian invited Calder to his studio, and it was there, in viewing a white wall with cardboard rectangles of varying colors tacked on it, that he was inspired to delve into the abstract. He felt the rectangles could be made "to oscillate in different directions, and at different amplitudes." The visit proved to be the "shock that started things," he said later. Within a few months he was making mobiles.

I was writing with greg from daddytypes last week about the Calder toys and Cirque Calder and he mentioned how much he loved Carlos Vilardebo's 1961 film of Calder performing his circus, and I remembered I had it on DVD somewhere in my collection of bootlegs, so I ripped it, converted it, and uploaded it to youtube in four-minute chunks. The video quality on my version was never great, so it's perfect for youtube. It is a remarkable film, not just for the ingenuity of its subject but for the gravity of seeing one of the true geniuses of the 20th century playing circus just like he did when he was an unknown young man:

That's part one. Here's part two; Part three; and Part four. It's a total of 18 minutes or so. My favorite part is when the lion shits and he covers it with sawdust.

Several Calder toys are still being manufactured and are for sale on the internet, including his elephant and cat puzzles, the kangaroo, the bull push toy, and, of course, the shark Juniper is playing with in the picture above. Those are expensive as hell, display pieces more than toys, really. But they are all the evidence I need that a well-engineered toy doesn't have to have microchips in it to be remarkable.

Copyright © 2005-2016 Sweet Juniper Media, Inc.

All Rights Reserved.

All Rights Reserved.

"Sweet Juniper" is a registered trademark.

No unauthorized reuse.

No unauthorized reuse.

Categories

- Friday Morning Street Urchin Blogging ( 107 )

- Detroit ( 60 )

- SAHD ( 34 )

- photography ( 30 )

- Thursday Morning Wood ( 25 )

- Halloween ( 23 )

- Thrift ( 18 )

- abandoned places ( 18 )

- terrifying nixon-era children's books ( 16 )

- Reminiscin' ( 15 )

- Sweet Juniper Media ( 11 )

- Wendell ( 10 )

- Design ( 9 )

- San Francisco ( 9 )

- nature fights back ( 9 )

- sleep ( 9 )

- if you ain't dutch you ain't much ( 8 )

- sentimental ( 7 )

- Music ( 6 )

- Parody ( 6 )

- birth story ( 6 )

- scrappers ( 6 )

- Sweet Juniper Tunes ( 5 )

- lawyering ( 5 )

- Zoo ( 4 )

- elegant leisure ( 4 )

- language ( 3 )

- feral houses ( 2 )

- theme parks of the damned ( 2 )

- zombies ( 1 )

Archives

- November 2017 ( 2 )

- December 2016 ( 1 )

- November 2016 ( 2 )

- December 2015 ( 1 )

- November 2015 ( 2 )

- December 2014 ( 1 )

- October 2014 ( 2 )

- April 2014 ( 1 )

- December 2013 ( 2 )

- November 2013 ( 1 )

- October 2013 ( 1 )

- September 2013 ( 2 )

- July 2013 ( 2 )

- June 2013 ( 1 )

- April 2013 ( 1 )

- March 2013 ( 3 )

- February 2013 ( 1 )

- January 2013 ( 1 )

- December 2012 ( 2 )

- November 2012 ( 1 )

- October 2012 ( 4 )

- September 2012 ( 2 )

- August 2012 ( 2 )

- July 2012 ( 1 )

- June 2012 ( 3 )

- May 2012 ( 1 )

- April 2012 ( 2 )

- March 2012 ( 1 )

- February 2012 ( 2 )

- January 2012 ( 1 )

- December 2011 ( 3 )

- November 2011 ( 3 )

- October 2011 ( 5 )

- September 2011 ( 3 )

- August 2011 ( 4 )

- July 2011 ( 4 )

- June 2011 ( 2 )

- May 2011 ( 4 )

- April 2011 ( 6 )

- March 2011 ( 7 )

- February 2011 ( 4 )

- January 2011 ( 4 )

- December 2010 ( 5 )

- November 2010 ( 7 )

- October 2010 ( 5 )

- September 2010 ( 4 )

- August 2010 ( 5 )

- July 2010 ( 7 )

- June 2010 ( 5 )

- May 2010 ( 5 )

- April 2010 ( 5 )

- March 2010 ( 4 )

- February 2010 ( 5 )

- January 2010 ( 5 )

- December 2009 ( 6 )

- November 2009 ( 5 )

- October 2009 ( 8 )

- September 2009 ( 9 )

- August 2009 ( 6 )

- July 2009 ( 9 )

- June 2009 ( 8 )

- May 2009 ( 8 )

- April 2009 ( 8 )

- March 2009 ( 12 )

- February 2009 ( 11 )

- January 2009 ( 9 )

- December 2008 ( 11 )

- November 2008 ( 9 )

- October 2008 ( 14 )

- September 2008 ( 11 )

- August 2008 ( 11 )

- July 2008 ( 12 )

- June 2008 ( 10 )

- May 2008 ( 9 )

- April 2008 ( 8 )

- March 2008 ( 10 )

- February 2008 ( 15 )

- January 2008 ( 12 )

- December 2007 ( 9 )

- November 2007 ( 12 )

- October 2007 ( 11 )

- September 2007 ( 13 )

- August 2007 ( 11 )

- July 2007 ( 8 )

- June 2007 ( 12 )

- May 2007 ( 10 )

- April 2007 ( 10 )

- March 2007 ( 12 )

- February 2007 ( 14 )

- January 2007 ( 12 )

- December 2006 ( 11 )

- November 2006 ( 10 )

- October 2006 ( 13 )

- September 2006 ( 8 )

- August 2006 ( 13 )

- July 2006 ( 13 )

- June 2006 ( 15 )

- May 2006 ( 13 )

- April 2006 ( 9 )

- March 2006 ( 10 )

- February 2006 ( 3 )

- January 2006 ( 5 )

- December 2005 ( 2 )

- November 2005 ( 8 )

- October 2005 ( 4 )

- September 2005 ( 1 )

- July 2005 ( 3 )