A long time ago I wrote a post lamenting the kind of dollhouses that were available on the market. At the time, Juniper wasn't even a year old, and things have gotten considerably better since then. In that old post I vowed to build Juniper her own dollhouse, and ever since my wife's cruel revelation about the woeful cardboard vehicles I make for Juniper, I have felt a need to redeem myself in terms of what I am able to make with my hands. So I decided to build Juniper a dollhouse that resembled our own home, a Mies van der Rohe shoe box whose lack of any ornament would make the job extremely simple.

The problem was, every time I visited one of those giant chain hardware stores, I would quickly grow intimidated and walk away before the guys in the smocks needled me into exposing my complete incompetence. All that talk about different kinds of saws really stresses me out. Besides, wood is freaking expensive. You'd think it didn't grow on trees.

I decided I was going to build the dollhouse out of scraps of wood that I could find wherever. Last weekend we were on the west side of the state, and I sniffed around the bargain bin outlets of Herman Miller and those other furniture companies over there. I found five heavy shelves that were the perfect length. They were $1.00 each. Then I needed to find some plexiglass for the window-walls, but all I could find were four sheets of translucent matte acrylic for $2.00 each. I spent a good chunk of Saturday morning with my dad in his auto body shop cutting the acrylic sheets and configuring the dollhouse. All week I have been using nap time to put it together, drilling holes in the acrylic and screwing at least 200 screws into the damn thing. I used toy blocks for the stairs and a leftover acrylic strip for the staircase. Just like our own floating staircase, they may look perilous, but they are solid: All in all, the dollhouse cost me about $15 to make, including screws. But considering that my woodworking experience consists of about an hour watching the New Yankee Workshop and maybe half an episode of Bob the Builder, I don't think it turned out too bad. I love it when minimalist taste, thrift, and complete lack of craftsmanship all come together to form a happy trifecta:

All in all, the dollhouse cost me about $15 to make, including screws. But considering that my woodworking experience consists of about an hour watching the New Yankee Workshop and maybe half an episode of Bob the Builder, I don't think it turned out too bad. I love it when minimalist taste, thrift, and complete lack of craftsmanship all come together to form a happy trifecta:

I am debating whether to make it look even more like our place on the outside, or just leave it kind of abstract and minimal. I am leaning towards the latter. What I like about dollhouses is that they are spaces designed solely for a kid's imagination. She lands airplanes on the roof and lets Wild Things climb the stairs. I don't want to dictate any of the terms inside, or buy these chairs. She really wants a potty for it though, so I'll probably do what we did to decorate our real house: buy a whole bunch of cheap vintage stuff from the 70s and let her put the furniture wherever she wants to.

I am debating whether to make it look even more like our place on the outside, or just leave it kind of abstract and minimal. I am leaning towards the latter. What I like about dollhouses is that they are spaces designed solely for a kid's imagination. She lands airplanes on the roof and lets Wild Things climb the stairs. I don't want to dictate any of the terms inside, or buy these chairs. She really wants a potty for it though, so I'll probably do what we did to decorate our real house: buy a whole bunch of cheap vintage stuff from the 70s and let her put the furniture wherever she wants to.

Yesterday I took Juniper to the Henry Ford Museum, and made the mistake of walking her through the 600-ton steam engines before we made it to the exhibit that I was there to see, the 50th-anniversary celebration of the Eames Lounge Chair, a vintage example of which we just revealed sits in our living room. I hadn't been to the Henry Ford since I was a kid, and I fell in love with it again. A Smithsonian for the upper Midwest, it has the Rosa Parks bus parked a few feet from the bloody rocking chair in which Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, itself not far from the car JFK was riding in when he got shot. Beyond these common objects grafted into history by the events that occurred within them, there are thousands of other common objects, long rows of automobiles and airplanes and bicycles built for ten and motorized roller skates, steam trains that dwarf every man, steam engines that propelled the first Ford assembly lines, airstream trailers and a R. Buckminster Fuller dymaxion house, all of it together such a wonderful celebration of American ingenuity and industry.

But I was there to see an exhibit about a chair I already owned. As Juniper sat in my arms and I read the placards under early Eames prototypes and molded-plywood splints, she began to whine, "Dada, can we see trains again? Dada, airplanes?" I was there for the minutia of the Eames exhibition, the letters Ray wrote to Charles on construction paper and the charcoal sketches of morphing shapes that would form the basis of so many famous chairs, but Juniper couldn't grasp why we would be looking at pictures of chairs when there were trains and dollhouses and airplanes to see. When we got to the star of the exhibit, the 1956 lounge chair owned by Herman Miller president D.J. Dupree, set under soft light on a spinning pedestal, Juniper looked at it and said, "That our chair. Juney go round and round?" I often spin her on the one in our living room.

Before I took her out of the exhibit to squeal at the most magnificent thing she had ever seen, the Oscar Mayer Wienermobile ("Dada, buy it? Juney drive it!"), I was struck by this 1959 ad showing a pajama-clad father sleeping with his infant child on his lap. The text reads, "Even if you don't have a two o'clock feeding at your house, we think you will appreciate the deep comfort of this rosewood and leather lounge chair designed by Charles Eames for Herman Miller":

For the last eight months, we have been living in a fishbowl. I don't mean that as some sort of metaphor about this blog and the way it allows you to peer into our lives, I mean literally, we live in a fishbowl. Two walls of our home are wall-to-wall, floor-to-ceiling windows. We throw no stones around here.

For the last eight months, we have been living in a fishbowl. I don't mean that as some sort of metaphor about this blog and the way it allows you to peer into our lives, I mean literally, we live in a fishbowl. Two walls of our home are wall-to-wall, floor-to-ceiling windows. We throw no stones around here.

Last October, we were honored to learn that the lovely Grace Bonney of Design*Sponge fame enjoys this blog, particularly the pictures of little Juniper. I am nothing but an unphotogenic man who had one photogenic sperm that met an egg inside my photogenic wife. I am not an artist, or a designer. For weeks Grace has been peeking into the beautiful homes of talented artists and designers. When she asked me if she could allow her readers a peek into our fishbowl, it was with some trepidation that we obliged. If you would like to share a peek inside our home, be sure to head over to Design*Sponge today. And go back. Every day. Grace always leads her readers to people and places and art worth seeing. I just hope we can live up to that standand.

For those visiting from Design*Sponge, this is a blog mostly about parenting. In downtown Detroit. I can be a curmudgeonly, cheap, bitter asshole sometimes. I can also be ridiculously sentimental. We started using the goofy nicknames years ago because I didn't want people from high school finding the blog and making fun of me. I just turned 30. My real name is Jim. Welcome.

Sweet Juniper's Alphabet

Posted by jdg | Thursday, February 01, 2007 | abecedaries , Design , Sweet Juniper Media

As you may have figured from that video Wood posted, we're big on the alphabet around here these days. This week I was really getting sick of all the stupid alphabet books we had been reading, so I decided to make my own. Don't get me wrong, I am a big fan of Nikki McClure's Awake to Nap and Michael De Feo's Alphabet City, but despite the latter's lovely urban scenery, the subject verbiage itself is a bit humdrum for my taste. Like most alphabet books, the words tend to be either zoological or agricultural. I wanted to create a book for a kid, like mine, who is growing up in a dirty-ass city and who already knows the names of all the animals in the zoo and in the Big Red Barn. De Feo (who did create the beautiful paste-ups for his book) simply doesn't use very many words that aren't that different from those in all of the other alphabet books I've seen. The letter N, for example, is represented in De Feo's book by a nest. Every alphabet book uses a nest for the letter N. Juniper and I seem to be in agreement that nests are kind of irrelevant. I feel it is much more important for her to identify other things that start with the letter N, such as ninjas: Now if our home is ever attacked by a group of numb-chuck-wielding, star-throwing ninjas, Juniper can shout out a warning that could save all our lives. The same is true for this one:

Now if our home is ever attacked by a group of numb-chuck-wielding, star-throwing ninjas, Juniper can shout out a warning that could save all our lives. The same is true for this one: You traditionalists can teach your kids about all the zebras all you want, but my kid is going to know how to identify a zombie wearing underwear as soon as she sees one. And anyone who has seen a Romero film knows how important a few seconds of warning can be when fending off zombies. The same theory works for mummies, pirates, robots, economists, vikings, and yeti. You won't find them in any other alphabet books, but you will find them in ours. I also threw in some hard words like Gnome and Knight just to mess with her head.

You traditionalists can teach your kids about all the zebras all you want, but my kid is going to know how to identify a zombie wearing underwear as soon as she sees one. And anyone who has seen a Romero film knows how important a few seconds of warning can be when fending off zombies. The same theory works for mummies, pirates, robots, economists, vikings, and yeti. You won't find them in any other alphabet books, but you will find them in ours. I also threw in some hard words like Gnome and Knight just to mess with her head.

Now I don't want to hear any bullshit about how my kid is going to need therapy or how I'm so politically incorrect etc. etc. ad nauseam. We get plenty of e-mails about that every week. If you have an inclination to point something like that out, just remember you're not as clever as you think you are. Seriously: yawn.

For the past few months whenever I see a painting or a stencil of something that would make a good subject word in an alphabet book, I have snapped a picture. I have so much gratitude for the amazing artists who are out there creating these beautiful works in our streets for little or no recognition, risking so much just to make our cities a little more colorful and interesting.

In a few days I'll probably post some pictures on flickr to show how I turned these images into an actual book, but for now if you have any interest in making one yourself, using or adapting any of the images, or just getting a closer look, click on the 4-paneled jpegs below for high-res downloadable images.

Juniper and I had a lot of fun making this (I knew which images to choose when she pointed at the screen and said, "who's THAT guy?"). Enjoy.

Juniper and I had a lot of fun making this (I knew which images to choose when she pointed at the screen and said, "who's THAT guy?"). Enjoy.

Original comments here

Every ethnicity should have its own theme park

Posted by jdg | Monday, September 11, 2006 | Design , if you ain't dutch you ain't much , theme parks of the damned , Thrift

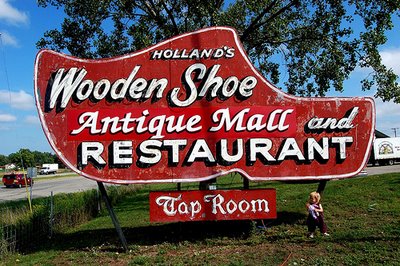

My wife spent her teen years in a place called Holland, Michigan, home of the annual "Tulip Time" Festival, a mysterious place called "Windmill Island," the original Russ' Restaurant, and reputably more churches per capita than any other place on earth. The local high school's mascot is the "Dutchmen." When Wood was a cheerleader she wore red underwear under her skirt that said "Dutch" in white letters across her ass. Wood's mother grew up in Holland, one of eight children in one of the few Catholic families in town. Wood and her mother both frequently dealt with blonde, blue-eyed Dutch Christian Reformed people telling them that they were "Catholic, not Christian." This drove them both nuts. When I first started dating Wood, her mom and stepdad would constantly make remarks about the "goddamn Dutch people" in Holland. It brought a secret thrill to me knowing that my mother in law's good little Irish girl was dating one of them. Wood's parents would have been so much happier if she would have just brought home a black guy. But finally I was the bad boy. A genetically-ingrained frugality and loads and loads of fundamentalist guilt may not be quite the same as a leather jacket and a motorcycle, but I worked with them best I could to appear a mildly dangerous Dutchman.

My wife spent her teen years in a place called Holland, Michigan, home of the annual "Tulip Time" Festival, a mysterious place called "Windmill Island," the original Russ' Restaurant, and reputably more churches per capita than any other place on earth. The local high school's mascot is the "Dutchmen." When Wood was a cheerleader she wore red underwear under her skirt that said "Dutch" in white letters across her ass. Wood's mother grew up in Holland, one of eight children in one of the few Catholic families in town. Wood and her mother both frequently dealt with blonde, blue-eyed Dutch Christian Reformed people telling them that they were "Catholic, not Christian." This drove them both nuts. When I first started dating Wood, her mom and stepdad would constantly make remarks about the "goddamn Dutch people" in Holland. It brought a secret thrill to me knowing that my mother in law's good little Irish girl was dating one of them. Wood's parents would have been so much happier if she would have just brought home a black guy. But finally I was the bad boy. A genetically-ingrained frugality and loads and loads of fundamentalist guilt may not be quite the same as a leather jacket and a motorcycle, but I worked with them best I could to appear a mildly dangerous Dutchman.

And now my mother in law's granddaughter is part them. Moo-hoo-ha-ha-ha.

In some ways though, I feel my mother in law's annoyance with my people is completely justified. I find repugnant so much of my forebears' fundamentalist Calvinism and intolerance. As I've written before, the Dutch people in western Michigan "left the Netherlands because the government was granting rights to Jews and Catholics and their church had grown too liberal. They are perhaps the only immigrant community in North America who left their native land because the government there had grown too tolerant for them." Sure there are tons of cool people in the Netherlands today, and I can't help but wonder if the country is so awesome because they shipped all their assholes off to Michigan in the last couple centuries.

But the Dutch in southwestern Michigan are not without their redeeming cultural institutions, such as the aforementioned tulip festival and, well, the restaurant with telephones on every table so you can call the kitchen yourself and avoid having to tip the waitress. But above all else, the mecca of Dutchdom in Holland is Dutch Village, a theme park designed to resemble a late-eighteenth-century Dutch town. At Dutch Village you can have a pair of "klompen" (wooden shoes) made for you, you can shop for Delft pottery, or dine at the Hungry Dutchman cafe. I have tried some traditional Dutch breakfast dish called balkenbrij, which turned out to be cow and sheep and pig's livers ground into a hash and fried on the griddle, and the waitress told me everyone she'd seen order it had eaten it with maple syrup. I'm sure it warmed the cockles of my grandfather's ghost's heart to see me eating that. That dude just could never get enough liver.

It does cost $10.00 to get into Dutch Village, but the website has convenient answers to the following frequently asked questions:

What are your admission rates? Do you offer any discounts on admission? What if it rains? Do I have to pay admission if I just want to shop? What is included in the admission price? Am I allowed to bring a picnic lunch?

Apparently these are the type of questions that Dutch people ask. Over and over again.

A little more than a week ago, we visited Holland (Wood's mom still lives there). I ignored the little Dutch boy on my shoulder and forked over that $10.00 without even trying for the AARP discount, so Juniper and I were able to spend an hour or so in Dutch village. Wood went wandering around the nearby outlet mall, but later she snuck into Dutch Village without paying. And I'm the cheap one? Well yes, because when she did it I was so freaking proud of her. I haven't uploaded photos in a week, so I'm just getting to these now: I like the little Dutch boy on this bathroom sign because he's clearly got to go himself. Either that or he already has, and he has just filled his pants. Remember back when people "Dutch rolled" their pants? That's what's keeping it all in.

I like the little Dutch boy on this bathroom sign because he's clearly got to go himself. Either that or he already has, and he has just filled his pants. Remember back when people "Dutch rolled" their pants? That's what's keeping it all in. It's just like Amsterdam, without the hookers and pot. If Amsterdam was built on ten acres in the middle of a vacant outlet mall's parking lot next to a state highway downwind of a Wal-Mart.

It's just like Amsterdam, without the hookers and pot. If Amsterdam was built on ten acres in the middle of a vacant outlet mall's parking lot next to a state highway downwind of a Wal-Mart. My mom has an identical picture of me as a baby sitting in this same stork's bundle. As far as my parents were concerned, this experience was all I needed to know about how babies were made. It's the most we ever talked about sex.

My mom has an identical picture of me as a baby sitting in this same stork's bundle. As far as my parents were concerned, this experience was all I needed to know about how babies were made. It's the most we ever talked about sex. The best thing about the southwestern Michigan is that there is mid-century Herman Miller molded fiberglass everywhere you look and nobody knows that it's cool. consider this wheelchair. I would practically chew off my own leg to get to ride around in one of those. It's an Eames shell chair on bicycle wheels with a footrest. It's like a Duchamp sculpture you can get pushed around in and you never have to worry about your next door neighbor ordering it from Design Within Reach. When I'm old I am totally moving to Dutch Village.

The best thing about the southwestern Michigan is that there is mid-century Herman Miller molded fiberglass everywhere you look and nobody knows that it's cool. consider this wheelchair. I would practically chew off my own leg to get to ride around in one of those. It's an Eames shell chair on bicycle wheels with a footrest. It's like a Duchamp sculpture you can get pushed around in and you never have to worry about your next door neighbor ordering it from Design Within Reach. When I'm old I am totally moving to Dutch Village. Since this moment, in all of Juniper's dreams, wherever she goes, she is pulled around in a little cart by a friendly dog. I have no doubt about that.

Since this moment, in all of Juniper's dreams, wherever she goes, she is pulled around in a little cart by a friendly dog. I have no doubt about that. One of the attractions is the Frisian Farmhouse, which is a historically accurate farmhouse filled with old Dutch crap, like the nineteenth-century Bugaboo above and this Stokke Kinderzeat prototype:

One of the attractions is the Frisian Farmhouse, which is a historically accurate farmhouse filled with old Dutch crap, like the nineteenth-century Bugaboo above and this Stokke Kinderzeat prototype: It's like a little baby prison, with a pisspot you can change every four hours or so. Modern Dutch design could learn a thing or two from the past. It's really too bad that only the good folks at Graco are still in touch with the important concept of baby imprisonment.

It's like a little baby prison, with a pisspot you can change every four hours or so. Modern Dutch design could learn a thing or two from the past. It's really too bad that only the good folks at Graco are still in touch with the important concept of baby imprisonment. In the background of this picture, you can see some old ladies dressed up in traditional Dutch costumes. Dutch Village is swarming with these old ladies. There are some younger ones too, and they all have real Dutch accents. In the farmhouse I encountered a young college student from the Netherlands who tried to tell me all about the traditional Dutch wares around him. Judging by his stoic performance, they clearly don't encounter a lot of visitors to Dutch Village who are there solely for the kitsch value. He was so serious with me, staying in character, that I started asking all these questions like, "Did you do something bad in the Netherlands? Is that why you're here?" and "Do the bosses make you sleep here?" That finally cracked his shit up. Then he had to go do this klompen dancing thing that totally made me lose respect for him. You just can't take a guy seriously when he's wearing giant wooden shoes.

In the background of this picture, you can see some old ladies dressed up in traditional Dutch costumes. Dutch Village is swarming with these old ladies. There are some younger ones too, and they all have real Dutch accents. In the farmhouse I encountered a young college student from the Netherlands who tried to tell me all about the traditional Dutch wares around him. Judging by his stoic performance, they clearly don't encounter a lot of visitors to Dutch Village who are there solely for the kitsch value. He was so serious with me, staying in character, that I started asking all these questions like, "Did you do something bad in the Netherlands? Is that why you're here?" and "Do the bosses make you sleep here?" That finally cracked his shit up. Then he had to go do this klompen dancing thing that totally made me lose respect for him. You just can't take a guy seriously when he's wearing giant wooden shoes.

Juniper was so pissed that these piles of fake cheese couldn't be toppled over. Believe me, she tried.

Juniper was so pissed that these piles of fake cheese couldn't be toppled over. Believe me, she tried. One of the best things about Dutch Village is the ability to check out a goat and walk with it throughout the entire park. Unfortunately this goat weighed twice as much as Juniper and had his own singular agenda.

One of the best things about Dutch Village is the ability to check out a goat and walk with it throughout the entire park. Unfortunately this goat weighed twice as much as Juniper and had his own singular agenda. This old pipe organ provides the music for the klompen dancing. Juniper stood there long after the dancing was over, tapping her palm and demanding "more, more more." I almost bought her some size 4 wooden shoes right then, I tell ya.

This old pipe organ provides the music for the klompen dancing. Juniper stood there long after the dancing was over, tapping her palm and demanding "more, more more." I almost bought her some size 4 wooden shoes right then, I tell ya. Here is a sculpture commemorating Pieter, the little boy who stuck his finger in the dike to save the Wal Mart, the Steak'n'Shake, and the Pier One Imports.

Here is a sculpture commemorating Pieter, the little boy who stuck his finger in the dike to save the Wal Mart, the Steak'n'Shake, and the Pier One Imports.

Calder toys

Posted by jdg | Monday, June 19, 2006 | Alexander Calder , calder , calder toys , calder's circus , Design

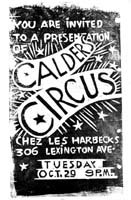

Wood braved the crowds of yuppies at the annual Design Within Reach blowout warehouse scratch-n-dent extravaganza in Union City this weekend, and all she got me was this totally awesome shark toy designed by Alexander Calder for a third of its normal price: Nothing I could write about Calder could justify the reverence I have for his artistic work; growing up I learned quickly to associate his name with those vibrant stabiles that bring so much life to public plazas, particularly La Grande Vitesse in the Grand Rapids, Michigan plaza that bears Calder's name, as well as the giant red Flamingo stabile that sits within Mies van der Rohe's federal plaza in Chicago, and Calder's Bent Propeller that was virtually destroyed in the plaza outside the World Trade Center on 9/11. And then there are his mobiles. The man invented the mobile. That means every nurseling for the last fifty years who has stared up at rotating, bobbing shapes above his crib has Calder to thank for the hours of entertainment. Sartre, in an essay on Calder, wrote that "a mobile is a little private celebration, an object defined by its movement and having no other existence. It is a flower that fades when it ceases to move, a 'pure play of movement' in the sense that we speak of a pure play of light."

Nothing I could write about Calder could justify the reverence I have for his artistic work; growing up I learned quickly to associate his name with those vibrant stabiles that bring so much life to public plazas, particularly La Grande Vitesse in the Grand Rapids, Michigan plaza that bears Calder's name, as well as the giant red Flamingo stabile that sits within Mies van der Rohe's federal plaza in Chicago, and Calder's Bent Propeller that was virtually destroyed in the plaza outside the World Trade Center on 9/11. And then there are his mobiles. The man invented the mobile. That means every nurseling for the last fifty years who has stared up at rotating, bobbing shapes above his crib has Calder to thank for the hours of entertainment. Sartre, in an essay on Calder, wrote that "a mobile is a little private celebration, an object defined by its movement and having no other existence. It is a flower that fades when it ceases to move, a 'pure play of movement' in the sense that we speak of a pure play of light."

Only recently did I learn that Calder began his artistic career by designing toys. In 1927 he designed a series of kinetic toys for the Gould Manufacturing Company of Oshkosh, Wisconsin that in their design bear witness to Calder's mechanical and artistic genius. Most of the toys are pulled by a string, and lurch along in various movements that mimic the movements of the creatures they were designed to represent: a frog, a seal, a skating bear, a kangaroo, a cow, a shark. Calder designed them to be pulled on axles that connected the wheels not at their center but at what are called "eccentric" points. Thus, the frog and the kangaroo hop. The duck bobs like real ducks do. And the shark lurches on its wheels, allowing its tail to shift back and forth like a fish navigating currents. Before embarking on his toymaking career, Calder graduated from the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey, with a degree in mechanical engineering. One can't help but speculate that this early application of engineering principles to a few deceptively simple toys ultimately led to his intricately balanced and wonderfully playful mobiles.

Only recently did I learn that Calder began his artistic career by designing toys. In 1927 he designed a series of kinetic toys for the Gould Manufacturing Company of Oshkosh, Wisconsin that in their design bear witness to Calder's mechanical and artistic genius. Most of the toys are pulled by a string, and lurch along in various movements that mimic the movements of the creatures they were designed to represent: a frog, a seal, a skating bear, a kangaroo, a cow, a shark. Calder designed them to be pulled on axles that connected the wheels not at their center but at what are called "eccentric" points. Thus, the frog and the kangaroo hop. The duck bobs like real ducks do. And the shark lurches on its wheels, allowing its tail to shift back and forth like a fish navigating currents. Before embarking on his toymaking career, Calder graduated from the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey, with a degree in mechanical engineering. One can't help but speculate that this early application of engineering principles to a few deceptively simple toys ultimately led to his intricately balanced and wonderfully playful mobiles. But there is a clear transition, and it is wonderful to behold: Calder's experimenting with various toy designs led to the development of a complex miniature circus in his studio. Calder had long been fascinated by the circus, and in his twenties he paid his way through art classes by selling a number of illustrations of the Barnum and Bailey's Circus to the National Police Gazette. In the late 1920s, Calder developed his own one-man circus, with tiny performers made of "cork, wire, wood, yarn, paper, string, and cloth," carefully engineered to walk tightropes, dance, tame lions, lift weights, and engage in gymnastics and acrobatics in and above the ring. Acting as omniscient ringmaster, Calder would manipulate the wire performers while his wife wound circus music on the gramophone in the background. While struggling as a more traditional artist in Paris, Calder began two-hour improvised performances of his Cirque Calder that recreated the performance of an actual circus. The show soon became a popular diversion among the Parisian avant-garde, and Calder began charging an entrance fee to see the big-top circus that could be packed into a suitcase. I like to imagine Calder's rented Montmartre studio on some smoky conglomerated pre-War Parisian night, filled with the likes of Jean Cocteau, Picasso, Joan Miro, James Joyce, Fernand Leger, Le Corbusier, Thomas Wolfe, and Andre Kertesz watching the young American perform his wire circus.

But there is a clear transition, and it is wonderful to behold: Calder's experimenting with various toy designs led to the development of a complex miniature circus in his studio. Calder had long been fascinated by the circus, and in his twenties he paid his way through art classes by selling a number of illustrations of the Barnum and Bailey's Circus to the National Police Gazette. In the late 1920s, Calder developed his own one-man circus, with tiny performers made of "cork, wire, wood, yarn, paper, string, and cloth," carefully engineered to walk tightropes, dance, tame lions, lift weights, and engage in gymnastics and acrobatics in and above the ring. Acting as omniscient ringmaster, Calder would manipulate the wire performers while his wife wound circus music on the gramophone in the background. While struggling as a more traditional artist in Paris, Calder began two-hour improvised performances of his Cirque Calder that recreated the performance of an actual circus. The show soon became a popular diversion among the Parisian avant-garde, and Calder began charging an entrance fee to see the big-top circus that could be packed into a suitcase. I like to imagine Calder's rented Montmartre studio on some smoky conglomerated pre-War Parisian night, filled with the likes of Jean Cocteau, Picasso, Joan Miro, James Joyce, Fernand Leger, Le Corbusier, Thomas Wolfe, and Andre Kertesz watching the young American perform his wire circus.

As his reputation among the avant-garde grew, Dutch painter Piet Mondrian invited Calder to his studio, and it was there, in viewing a white wall with cardboard rectangles of varying colors tacked on it, that he was inspired to delve into the abstract. He felt the rectangles could be made "to oscillate in different directions, and at different amplitudes." The visit proved to be the "shock that started things," he said later. Within a few months he was making mobiles.

I was writing with greg from daddytypes last week about the Calder toys and Cirque Calder and he mentioned how much he loved Carlos Vilardebo's 1961 film of Calder performing his circus, and I remembered I had it on DVD somewhere in my collection of bootlegs, so I ripped it, converted it, and uploaded it to youtube in four-minute chunks. The video quality on my version was never great, so it's perfect for youtube. It is a remarkable film, not just for the ingenuity of its subject but for the gravity of seeing one of the true geniuses of the 20th century playing circus just like he did when he was an unknown young man:

That's part one. Here's part two; Part three; and Part four. It's a total of 18 minutes or so. My favorite part is when the lion shits and he covers it with sawdust.

Several Calder toys are still being manufactured and are for sale on the internet, including his elephant and cat puzzles, the kangaroo, the bull push toy, and, of course, the shark Juniper is playing with in the picture above. Those are expensive as hell, display pieces more than toys, really. But they are all the evidence I need that a well-engineered toy doesn't have to have microchips in it to be remarkable.

Upper playgrounds

Posted by jdg | Monday, June 12, 2006 | Design , Isamu Noguchi , Nogucji playgrounds , playscapes

Six months ago, we didn't have much use for playgrounds; if we came across one with infant swings, I might let Juniper slump and squeal through the air, but there wasn't much else she could do. Nowadays, our life revolves around playgrounds: if we go anywhere in the city, we must make sure there is a playground nearby or there will be hell to pay. We live near Golden Gate Park, the site of the nation's oldest public playground, built in 1887. When Juniper was four days old, we took her for her first walk in the park and ended up in the playground, watching the toddlers and older kids run around, and I looked at my four-day-old daughter and couldn't imagine how she could ever be old enough to play in any of the awesome vintage 70s equipment that filled the giant playground. Turns out she wouldn't be. Not so long ago, we took her there only to discover it was gone. A rental chain-link fence prevented entry, and through the fence you could see that all of the great old equipment had disappeared. The slides: gone. The swings: gone. The kick-ass hexagonal honeycomb space maze: gone.

We live near Golden Gate Park, the site of the nation's oldest public playground, built in 1887. When Juniper was four days old, we took her for her first walk in the park and ended up in the playground, watching the toddlers and older kids run around, and I looked at my four-day-old daughter and couldn't imagine how she could ever be old enough to play in any of the awesome vintage 70s equipment that filled the giant playground. Turns out she wouldn't be. Not so long ago, we took her there only to discover it was gone. A rental chain-link fence prevented entry, and through the fence you could see that all of the great old equipment had disappeared. The slides: gone. The swings: gone. The kick-ass hexagonal honeycomb space maze: gone.

I nearly shed a tear that day, knowing that we would no longer be living in San Francisco when the new playground would be completed, but also knowing that they would inevitably replace it with the sterile, formulaic, lawyer/insurance-company-approved plastic playground monstrosities that are ubiquitous on most playgrounds today.

In our informal survey of other San Francisco playgrounds, I have realized that, like dollhouses, playgrounds are almost universally void of good design. If it's not the uninspired, safe plastic structures that are little more than exersaucers on growth hormones, it's a typical clunky 80s wooden jungle gym. I did find an awesome 70sish playground in the Fillmore with this Calder-esque climbing structure and these vertical tubes. It struck me that playgrounds have so much untapped potential for great design. Innovation seems limited to adding things like 4-foot climbing walls and flashy moving parts that inevitably break. Is it possible for a playground to be functional, fun and beautiful?

I just finished reading a long-lost screenplay for Charlie Chaplin's tramp character written by James Agee in the 1940s. The film was never made (by the time Agee had written it, Chaplin felt he was too old to play the tramp) but it could have been. Reading the screenplay, you can't help but think, "damn this would have been an amazing film." This got me thinking about all the great creative acts that, for one reason or another, never came into being. To architects and designers, this must happen all the time, when unrealized projects and plans just can't be brought to reality for any number of reasons.

I did a bit of poking around, and learned that the great sculptor, designer, and landscape architect Isamu Noguchi created a number of unrealized playgrounds. They are an important, but little-considered part of his work, which Noguchi himself acknowledged as "the kernel out of which have grown all my ideas relating sculpture to the earth." Noguchi believed children's playgrounds should be "sculptural landscapes." Only one of his many playground designs was ever actually built in America, the Playscapes playground completed in 1976 at Piedmont Park, in Atlanta, Georgia. I have never been there, but if any readers have seen it or been there I'd love to hear their impressions. From the pictures I have seen, it looks really cool.

I did a bit of poking around, and learned that the great sculptor, designer, and landscape architect Isamu Noguchi created a number of unrealized playgrounds. They are an important, but little-considered part of his work, which Noguchi himself acknowledged as "the kernel out of which have grown all my ideas relating sculpture to the earth." Noguchi believed children's playgrounds should be "sculptural landscapes." Only one of his many playground designs was ever actually built in America, the Playscapes playground completed in 1976 at Piedmont Park, in Atlanta, Georgia. I have never been there, but if any readers have seen it or been there I'd love to hear their impressions. From the pictures I have seen, it looks really cool.

The first playground Noguchi was commissioned to design was a "play mountain" in New York City, which was rejected in 1933 by the powerful New York City Parks Commissioner Robert Moses, a dude who apparently hated modern art even more than my dad. For nearly 30 years, Moses thwarted Noguchi's designs for several New York City playgrounds. His model for a swingset with multiple lengths of swing was originally designed for an unrealized Hawaiian playground, but was met with harsh criticism for its potential danger when he proposed it for another New York playground in 1939. The design has since been successfully incorporated into Noguchi playgrounds in Atlanta and Japan.

The first playground Noguchi was commissioned to design was a "play mountain" in New York City, which was rejected in 1933 by the powerful New York City Parks Commissioner Robert Moses, a dude who apparently hated modern art even more than my dad. For nearly 30 years, Moses thwarted Noguchi's designs for several New York City playgrounds. His model for a swingset with multiple lengths of swing was originally designed for an unrealized Hawaiian playground, but was met with harsh criticism for its potential danger when he proposed it for another New York playground in 1939. The design has since been successfully incorporated into Noguchi playgrounds in Atlanta and Japan. Conscious of the criticism that his modern geometric sculpture would cause injuries to children, Noguchi's next project was a more contoured, gentle landscape sculpture. Noguchi said it "would be proof against any serious accidents, being made of entirely earth modulations. Exercise was to be derived automatically in running up and down the curved surfaces. There were various areas of interest, for hiding, for sliding, for games." This playground was killed by NYC officials in 1941. Noguchi's next Manhattan project was a playground at the United Nations headquarters for the delegates' children. Noguchi took the project in 1952 because he thought Moses would not have jurisdiction to kill a project at the U.N. But Noguchi underestimated Moses, who called its design a "hillside rabbit warren" and made su

Conscious of the criticism that his modern geometric sculpture would cause injuries to children, Noguchi's next project was a more contoured, gentle landscape sculpture. Noguchi said it "would be proof against any serious accidents, being made of entirely earth modulations. Exercise was to be derived automatically in running up and down the curved surfaces. There were various areas of interest, for hiding, for sliding, for games." This playground was killed by NYC officials in 1941. Noguchi's next Manhattan project was a playground at the United Nations headquarters for the delegates' children. Noguchi took the project in 1952 because he thought Moses would not have jurisdiction to kill a project at the U.N. But Noguchi underestimated Moses, who called its design a "hillside rabbit warren" and made su re the playground would never get built by refusing to allow the city to erect a necessary protective fence on the East River-side of the playground. Noguchi described it as "A jungle gym transformed into an enormous basket that encourages the most complex ascents and all but obviates falls. In other words, the playground, instead of telling the child what to do (swing here, climb there) becomes a place for endless exploration, of endless opportunity for changing play. And it is a thing of beauty as the modern artist has found beauty in the modern world."

re the playground would never get built by refusing to allow the city to erect a necessary protective fence on the East River-side of the playground. Noguchi described it as "A jungle gym transformed into an enormous basket that encourages the most complex ascents and all but obviates falls. In other words, the playground, instead of telling the child what to do (swing here, climb there) becomes a place for endless exploration, of endless opportunity for changing play. And it is a thing of beauty as the modern artist has found beauty in the modern world." In 1961, Noguchi had a final opportunity to design a playground in New York City, this time for Riverside Park in collaboration with the architect Louis I. Kahn. After a long, drawn-out process of objections and re-designs, Noguchi's resolve and faith in his design and philosophy of playgrounds as "sculptural landscapes" was deepened. He said, "I later came to feel that children should not be restricted to fenced-in concrete play areas, and that some parks or parts of some parks, should become 'play gardens.'" But like the others, the Riverside Park project was killed by the bureaucrats.

In 1961, Noguchi had a final opportunity to design a playground in New York City, this time for Riverside Park in collaboration with the architect Louis I. Kahn. After a long, drawn-out process of objections and re-designs, Noguchi's resolve and faith in his design and philosophy of playgrounds as "sculptural landscapes" was deepened. He said, "I later came to feel that children should not be restricted to fenced-in concrete play areas, and that some parks or parts of some parks, should become 'play gardens.'" But like the others, the Riverside Park project was killed by the bureaucrats.

Several Noguchi playgrounds have been built in Japan (one in Sapporo, and one at the Kodomo no Kuni in Yokohama), and they show how Noguchi's sensibilities for landscape and play developed through the course of his frustrating New York experiences to create something truly wonderful. The play mountain and playground at Moerenuma Park, in particular, built on a reclaimed landfill, are really a complete testament to his full vision. These pictures show how wonderful playgrounds could be if we listened to rather than frustrate visionaries like Noguchi, who actually saw playgrounds as projects worthy of great design:

My wonderful and well-meaning sister bought Juniper this animatronic frog toddler named "Baby Tad." It's part of that unholy bastard progeny of Teddy Ruxpin and a Speak-n-Spell, you know, computerized toys that are supposed to be both educational and cuddly. Juniper, of course, loves it. It has become clear that Juniper needs an aunt like my sister, capable of softening the effects of a draconian upbringing by parents who dress her like a Bavarian Disco Baby, refuse to let her watch normal television and only buy her wooden toys from the Jura region of eastern France.

My wonderful and well-meaning sister bought Juniper this animatronic frog toddler named "Baby Tad." It's part of that unholy bastard progeny of Teddy Ruxpin and a Speak-n-Spell, you know, computerized toys that are supposed to be both educational and cuddly. Juniper, of course, loves it. It has become clear that Juniper needs an aunt like my sister, capable of softening the effects of a draconian upbringing by parents who dress her like a Bavarian Disco Baby, refuse to let her watch normal television and only buy her wooden toys from the Jura region of eastern France.

Tad always manages to find his way into the bedroom during the evening routine, broadcasting tinny microchip versions of Robert Schumann's Traumerei and Liszt's Liebestraum, signaling the onset of sleep and building all those classical music braincells, mais naturellement. He is also programmed to talk in a voice that a creepy 40-year-old white woman would use to talk to her cat, which is odd because according to his tag, Tad is a native of Bangladesh. Tad says things like, "Peekaboo, I see you!," "I wuv you!" and "Let's Snuggle!"

After we've put Juniper down for the night (she is totally sleeping rock solid for 10.5/11 hours now, by the way), Tad gets abandoned on the floor or on our bed. When Wood and I go to bed at around midnight, inevitably one of us steps on Baby Tad, starting a cycle of flashing lights or an annoying rendition of Hickory Dickory Dock. "Get that asshole Tad out of here!" I said the first time that happened. We have since taken to calling him That Asshole Tad all the time.

Last night, in a post-coital moment of clarity, I realized that Tad had been in the bed with us for the entire act. Get that asshole Tad out of the bed! I said and tossed him across the room. Wood put her arm around me, put one leg between both of mine, and I felt her hot breath on the back of my neck.

Then, in a pitch-perfect imitation of that asshole Tad she said, "Let's snuggle!"