Six months ago, we didn't have much use for playgrounds; if we came across one with infant swings, I might let Juniper slump and squeal through the air, but there wasn't much else she could do. Nowadays, our life revolves around playgrounds: if we go anywhere in the city, we must make sure there is a playground nearby or there will be hell to pay. We live near Golden Gate Park, the site of the nation's oldest public playground, built in 1887. When Juniper was four days old, we took her for her first walk in the park and ended up in the playground, watching the toddlers and older kids run around, and I looked at my four-day-old daughter and couldn't imagine how she could ever be old enough to play in any of the awesome vintage 70s equipment that filled the giant playground. Turns out she wouldn't be. Not so long ago, we took her there only to discover it was gone. A rental chain-link fence prevented entry, and through the fence you could see that all of the great old equipment had disappeared. The slides: gone. The swings: gone. The kick-ass hexagonal honeycomb space maze: gone.

We live near Golden Gate Park, the site of the nation's oldest public playground, built in 1887. When Juniper was four days old, we took her for her first walk in the park and ended up in the playground, watching the toddlers and older kids run around, and I looked at my four-day-old daughter and couldn't imagine how she could ever be old enough to play in any of the awesome vintage 70s equipment that filled the giant playground. Turns out she wouldn't be. Not so long ago, we took her there only to discover it was gone. A rental chain-link fence prevented entry, and through the fence you could see that all of the great old equipment had disappeared. The slides: gone. The swings: gone. The kick-ass hexagonal honeycomb space maze: gone.

I nearly shed a tear that day, knowing that we would no longer be living in San Francisco when the new playground would be completed, but also knowing that they would inevitably replace it with the sterile, formulaic, lawyer/insurance-company-approved plastic playground monstrosities that are ubiquitous on most playgrounds today.

In our informal survey of other San Francisco playgrounds, I have realized that, like dollhouses, playgrounds are almost universally void of good design. If it's not the uninspired, safe plastic structures that are little more than exersaucers on growth hormones, it's a typical clunky 80s wooden jungle gym. I did find an awesome 70sish playground in the Fillmore with this Calder-esque climbing structure and these vertical tubes. It struck me that playgrounds have so much untapped potential for great design. Innovation seems limited to adding things like 4-foot climbing walls and flashy moving parts that inevitably break. Is it possible for a playground to be functional, fun and beautiful?

I just finished reading a long-lost screenplay for Charlie Chaplin's tramp character written by James Agee in the 1940s. The film was never made (by the time Agee had written it, Chaplin felt he was too old to play the tramp) but it could have been. Reading the screenplay, you can't help but think, "damn this would have been an amazing film." This got me thinking about all the great creative acts that, for one reason or another, never came into being. To architects and designers, this must happen all the time, when unrealized projects and plans just can't be brought to reality for any number of reasons.

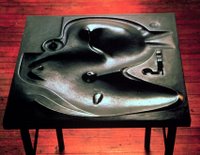

I did a bit of poking around, and learned that the great sculptor, designer, and landscape architect Isamu Noguchi created a number of unrealized playgrounds. They are an important, but little-considered part of his work, which Noguchi himself acknowledged as "the kernel out of which have grown all my ideas relating sculpture to the earth." Noguchi believed children's playgrounds should be "sculptural landscapes." Only one of his many playground designs was ever actually built in America, the Playscapes playground completed in 1976 at Piedmont Park, in Atlanta, Georgia. I have never been there, but if any readers have seen it or been there I'd love to hear their impressions. From the pictures I have seen, it looks really cool.

I did a bit of poking around, and learned that the great sculptor, designer, and landscape architect Isamu Noguchi created a number of unrealized playgrounds. They are an important, but little-considered part of his work, which Noguchi himself acknowledged as "the kernel out of which have grown all my ideas relating sculpture to the earth." Noguchi believed children's playgrounds should be "sculptural landscapes." Only one of his many playground designs was ever actually built in America, the Playscapes playground completed in 1976 at Piedmont Park, in Atlanta, Georgia. I have never been there, but if any readers have seen it or been there I'd love to hear their impressions. From the pictures I have seen, it looks really cool.

The first playground Noguchi was commissioned to design was a "play mountain" in New York City, which was rejected in 1933 by the powerful New York City Parks Commissioner Robert Moses, a dude who apparently hated modern art even more than my dad. For nearly 30 years, Moses thwarted Noguchi's designs for several New York City playgrounds. His model for a swingset with multiple lengths of swing was originally designed for an unrealized Hawaiian playground, but was met with harsh criticism for its potential danger when he proposed it for another New York playground in 1939. The design has since been successfully incorporated into Noguchi playgrounds in Atlanta and Japan.

The first playground Noguchi was commissioned to design was a "play mountain" in New York City, which was rejected in 1933 by the powerful New York City Parks Commissioner Robert Moses, a dude who apparently hated modern art even more than my dad. For nearly 30 years, Moses thwarted Noguchi's designs for several New York City playgrounds. His model for a swingset with multiple lengths of swing was originally designed for an unrealized Hawaiian playground, but was met with harsh criticism for its potential danger when he proposed it for another New York playground in 1939. The design has since been successfully incorporated into Noguchi playgrounds in Atlanta and Japan. Conscious of the criticism that his modern geometric sculpture would cause injuries to children, Noguchi's next project was a more contoured, gentle landscape sculpture. Noguchi said it "would be proof against any serious accidents, being made of entirely earth modulations. Exercise was to be derived automatically in running up and down the curved surfaces. There were various areas of interest, for hiding, for sliding, for games." This playground was killed by NYC officials in 1941. Noguchi's next Manhattan project was a playground at the United Nations headquarters for the delegates' children. Noguchi took the project in 1952 because he thought Moses would not have jurisdiction to kill a project at the U.N. But Noguchi underestimated Moses, who called its design a "hillside rabbit warren" and made su

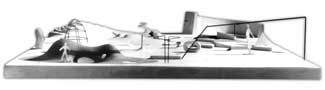

Conscious of the criticism that his modern geometric sculpture would cause injuries to children, Noguchi's next project was a more contoured, gentle landscape sculpture. Noguchi said it "would be proof against any serious accidents, being made of entirely earth modulations. Exercise was to be derived automatically in running up and down the curved surfaces. There were various areas of interest, for hiding, for sliding, for games." This playground was killed by NYC officials in 1941. Noguchi's next Manhattan project was a playground at the United Nations headquarters for the delegates' children. Noguchi took the project in 1952 because he thought Moses would not have jurisdiction to kill a project at the U.N. But Noguchi underestimated Moses, who called its design a "hillside rabbit warren" and made su re the playground would never get built by refusing to allow the city to erect a necessary protective fence on the East River-side of the playground. Noguchi described it as "A jungle gym transformed into an enormous basket that encourages the most complex ascents and all but obviates falls. In other words, the playground, instead of telling the child what to do (swing here, climb there) becomes a place for endless exploration, of endless opportunity for changing play. And it is a thing of beauty as the modern artist has found beauty in the modern world."

re the playground would never get built by refusing to allow the city to erect a necessary protective fence on the East River-side of the playground. Noguchi described it as "A jungle gym transformed into an enormous basket that encourages the most complex ascents and all but obviates falls. In other words, the playground, instead of telling the child what to do (swing here, climb there) becomes a place for endless exploration, of endless opportunity for changing play. And it is a thing of beauty as the modern artist has found beauty in the modern world." In 1961, Noguchi had a final opportunity to design a playground in New York City, this time for Riverside Park in collaboration with the architect Louis I. Kahn. After a long, drawn-out process of objections and re-designs, Noguchi's resolve and faith in his design and philosophy of playgrounds as "sculptural landscapes" was deepened. He said, "I later came to feel that children should not be restricted to fenced-in concrete play areas, and that some parks or parts of some parks, should become 'play gardens.'" But like the others, the Riverside Park project was killed by the bureaucrats.

In 1961, Noguchi had a final opportunity to design a playground in New York City, this time for Riverside Park in collaboration with the architect Louis I. Kahn. After a long, drawn-out process of objections and re-designs, Noguchi's resolve and faith in his design and philosophy of playgrounds as "sculptural landscapes" was deepened. He said, "I later came to feel that children should not be restricted to fenced-in concrete play areas, and that some parks or parts of some parks, should become 'play gardens.'" But like the others, the Riverside Park project was killed by the bureaucrats.

Several Noguchi playgrounds have been built in Japan (one in Sapporo, and one at the Kodomo no Kuni in Yokohama), and they show how Noguchi's sensibilities for landscape and play developed through the course of his frustrating New York experiences to create something truly wonderful. The play mountain and playground at Moerenuma Park, in particular, built on a reclaimed landfill, are really a complete testament to his full vision. These pictures show how wonderful playgrounds could be if we listened to rather than frustrate visionaries like Noguchi, who actually saw playgrounds as projects worthy of great design: