My first real job was washing dishes and bussing tables at Russ' Restaurant, where I earned a busboy's wage of $2.65 an hour. At the end of the night, I was supposed to get a ten-percent cut of each waitress' tips, which they would leave for me in a little white paper bag under the time clock. Sometimes a paper bag would only have a quarter and two dimes in it. Other times I might see $1.65 or more. With five waitresses on the floor, I eventually had to complain to the manager, Rod, that I wasn't making minimum wage. He smiled at me and told me that he, too, had started as a busboy at a Russ' restaurant in Holland, Michigan, but he worked hard and didn't complain and look at him now: he drives a Cadillac. He said if I worked hard, I might expect the same.

In other words, he told me to shut the fuck up and get back to my sink full of soggy french fries and greasy water that smelled like thousand island dressing and meat. One time, one of the waitresses came up behind me, slipped her arms under mine to grab my nipples and whisper in my ear: "what would you do if I got naked and climbed into that sink right there?" I looked at the foetid detritus of several dozen house salads and chicken bones floating in the murky, malodorous sludge. "Um. . ." I said, and she cackled and went back out on the floor.

God she scared the crap out of 16-year-old me.

One of my friends ended up regularly fucking her out in the parking lot during their 15-minute breaks. Restaurants are such hornet's nests of sexual depravity. When she cheated on him with another line cook my friend and a buddy got really drunk and broke into his house and tore it apart. They said they would have killed him had he been there. They both got probation.

Do I think the waitresses were stiffing me on the tips? Probably. Most of them were in their forties, supporting both their broken families and their addiction to Basic Ultra Light 100's on the same $2.65 plus tips I was making. Their nametags said things like Mabel and Rita. To their credit, Russ' was a Dutch restaurant whose most loyal customers usually needed to be wheeled in from a nursing home van. While pushing my bus cart around the restaurant I always had to be careful not to knock the tubes out from the various oxygen tank carts that lined the aisles. If most elderly folks on fixed incomes are frugal, you can imagine what old Dutch people are like. Four old Dutchies would each order (on separate checks) a $1.65 cup of ham-n-bean soup, each ask for six packs of saltines, and then each leave a dime and a nickel for a tip. I know all this because I used to clear their tables. Rumor was that the first Russ' restaurant on Chicago Drive in Holland, Michigan had telephones installed in every booth so customers could call the kitchen and order their food directly with the cooks. This was set up so no one would ever have to leave a tip. Russ' mascot was Russ, a Dutch boy more annoying than the bowl-headed chap on the paintcans, a clog-wearing punk carrying a gigantic burger through the tulips as though it were his reward for sticking his finger in the goddamn dike. I'll never forget one evening in July when the manager pulled me away from my buscart and told me he had a "special duty" for me that evening. He had a big gap between his top front teeth and he smiled when he pulled some red and blue clothes and a pair of wooden shoes from a bag. "Look what I've got," he said with aplomb. "You get to be the Russ tonight!"

Russ' mascot was Russ, a Dutch boy more annoying than the bowl-headed chap on the paintcans, a clog-wearing punk carrying a gigantic burger through the tulips as though it were his reward for sticking his finger in the goddamn dike. I'll never forget one evening in July when the manager pulled me away from my buscart and told me he had a "special duty" for me that evening. He had a big gap between his top front teeth and he smiled when he pulled some red and blue clothes and a pair of wooden shoes from a bag. "Look what I've got," he said with aplomb. "You get to be the Russ tonight!"

I should have walked out right then.

But I was a weak-willed sonofabitch back in those days, scared of a guy named Rod with a clip-on tie and a ten-year-old Cadillac. I put on the pants, the hat, the neckerchief, and the wooden shoes (which were about two sizes too small) and held a giant sign that said, 3-piece chicken dinner, w/ fries & slaw, only $4.99! in front of the restaurant on main street, certain that every girl in my high school was driving by, laughing. People yelled things. Flipped me off. Honked. When it was a slow night and nobody needed any tables bussed, Rod would pull out the Russ costume to remedy it.

To this day, whenever I see someone dressed as a banana or a hotdog, or some woman dressed up like the statue of liberty outside an accountant's office during tax time, I am haunted by the familiar look of quiet desperation in their eyes.

The Russ

Posted by jdg | Friday, June 30, 2006 | if you ain't dutch you ain't much , Reminiscin' , ThriftFriday Morning Street Urchin Blogging

Posted by jdg | Friday, June 30, 2006 | Friday Morning Street Urchin Blogging

Juniper woke up this morning at 5:20 a.m. Wood woke with a migraine. I can't put into words how annoying it is to have to wake up at 5:20 a.m. because your kid thinks it's a downright bully time to make you read her Runaway Bunny six times in a row, primarily because Mr. Nice Guy has already described it so perfectly:

"so the kid woke up at 5:30 this morning. sometimes she does this. other times she sleeps till 6:30. the raw power of that single 60 minutes is astonishing to me. the hour between 5:30 and 6:30 has such magical attributes that if you sleep during it, you wake up refreshed. if you don't, you wake up feeling like someone has crapped in your mouth."

He then goes on to describe an early-morning Brooklyn encounter nearly as disturbing as that time Juniper and I stumbled across two pantsless homeless guys distracted away from their shopping cart caravans just long enough to reenact the "piggy" scene from Deliverance in the woods of Golden Gate Park. Read it.

I have a new post up at the Blogfathers.

And as long as I'm just linking today, check out shisomama: this lady makes great collages daily, her kid's name is Otis and he has a haircut so hip I tried to explain it to the chick who charges me $70 every couple months to make me look like I perpetually just crawled out of bed. Clearly, this is a blog I was meant to love.

Oh, and I'm cooking up something big for tomorrow hopefully.

This morning I put on an old blue coat that four years ago my supervisors at work told me not to wear because it looked like it had been "purchased at a Goodwill." They were unaware, perhaps, that I believe Goodwill almost universally overprices its garments, and that it was probably purchased at the Salvation Army instead. Besides, before I could say that, they had moved on to telling me to get a haircut.

This morning I put on an old blue coat that four years ago my supervisors at work told me not to wear because it looked like it had been "purchased at a Goodwill." They were unaware, perhaps, that I believe Goodwill almost universally overprices its garments, and that it was probably purchased at the Salvation Army instead. Besides, before I could say that, they had moved on to telling me to get a haircut.

While standing on the bus this morning I leaned my nose into the bicep of my upstretched arm and smelled an odor in the coat that reminded me of walking past a homeless man. After four wet winters in my San Francisco closet the coat had reverted to its natural state of beautiful thriftstoriness. For some reason this made me feel very happy.

In little more than a month I intend to set aflame two weeks' worth of 15.5/33 Ike Behar shirts that I never want to wear again. And I will let my hair grow long and wander through the wilderness in the skin of a lion, and all that jazz.

We had hoped to start this past weekend with a celebration, but it didn't work out that way. After putting an offer on another house last Thursday, we thought we would be in contract by Friday afternoon. Instead, we spent all day Thursday and all day Friday waiting for our realtor to contact us. Turns out she didn't convey our offer as we had asked her to and then she underwent a lame effort to cover up her mistakes, primarily by not returning our phone calls or e-mails. When I finally got in touch with her and confronted her about what happened she told me it was inappropriate for me to "interrogate" her and said she wished "my mother could hear the way" I was speaking to her. She told me I was being disrespectful (this, after being incommunicato for more than 24 hours while our offer was out and then telling us our offer was "foolish") .

I wanted to say, "When I'm being disrespectful, trust me, you'll know it." But I didn't. I was uncharacteristically civil when I fired her first thing Saturday morning.

On Saturday we "ran into" Leah and Simon from a girl and a boy. Self-acknowledged as "baby crazy," Leah is a veteran blogger and one of our readers and Simon is such a good sport he arranged for a secret encounter with Wood and I, despite the fact that if I were him I would hate us. Leah has powerful Utah genes that are propelling her towards parenthood, and reading Sweet Juniper doesn't help much there, I guess. It seems she thinks we make parenting look tolerable. I love that people without kids read this blog, although if I were childless, this blog would make me throw up in my mouth every morning. Either that or I would read it just to make fun of my sappy ass. I know many "parenting" blogs have regular non-parent readers. I sometimes wonder what it is about this blog that makes it interesting to anyone, let alone people who aren't just here to commiserate about shitty sleep schedules and dirty diapers.

Sunday was the gay pride parade, and though it wasn't quite as exciting for us as last year (no surprisingly friendly gay barbarians), it's always great to see how the whole city rolls out the welcome mat and the rainbow flags and so many people celebrate gay culture and gay rights on such a huge scale. It reminds me that this society has been slowly arcing towards greater equality, and that heavy resistance is often a sign of desperation against the inevitable. Pride week always gives me more hope that soon every couple who wants to be married or raise kids together will be able to do so with the same legal rights as any other and that someday all the people out there who think it's any of their business to deny others such rights will be remembered just as we remember those crowds of saps you see in newsreel footage from the 50s being held back by the national guard while they hurl obscenities at little black girls just trying to go to school.

Friday Morning Street Urchin Blogging

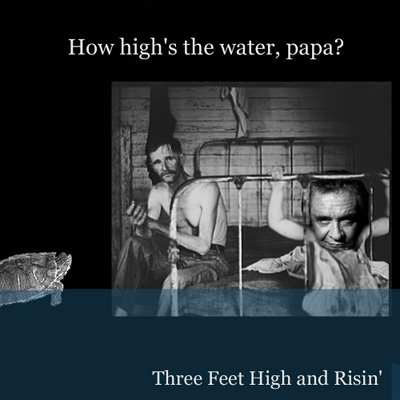

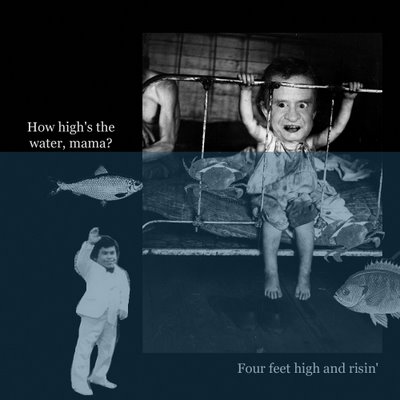

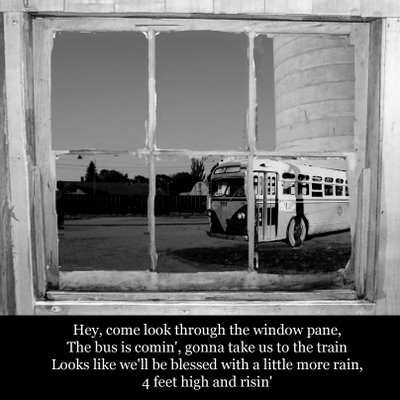

Posted by jdg | Friday, June 23, 2006 | Friday Morning Street Urchin BloggingThe children's books you wish celebrities would write, Vol. 3: "The Flood," by Johnny Cash

Posted by jdg | Wednesday, June 21, 2006 | celebrity children's books , Johnny Cash , Sweet Juniper Media

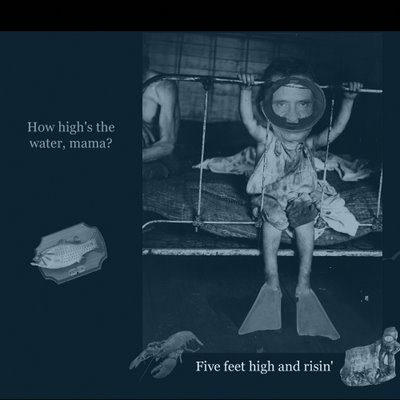

This month's edition of Sweet Juniper's children's books that you wish celebrities would write: The Johnny Cash board book, as promised.

Flickr set here. I modified Walker Evans photographs for most of the backgrounds, and changed the lyrics around a bit to give it a happy ending. Thanks to Her Bad Mother for suggesting Five Feet High and Risin' last month.

Flickr set here. I modified Walker Evans photographs for most of the backgrounds, and changed the lyrics around a bit to give it a happy ending. Thanks to Her Bad Mother for suggesting Five Feet High and Risin' last month.

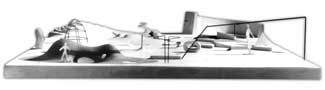

Calder toys

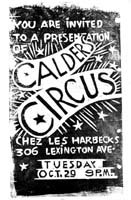

Posted by jdg | Monday, June 19, 2006 | Alexander Calder , calder , calder toys , calder's circus , Design

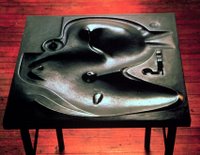

Wood braved the crowds of yuppies at the annual Design Within Reach blowout warehouse scratch-n-dent extravaganza in Union City this weekend, and all she got me was this totally awesome shark toy designed by Alexander Calder for a third of its normal price: Nothing I could write about Calder could justify the reverence I have for his artistic work; growing up I learned quickly to associate his name with those vibrant stabiles that bring so much life to public plazas, particularly La Grande Vitesse in the Grand Rapids, Michigan plaza that bears Calder's name, as well as the giant red Flamingo stabile that sits within Mies van der Rohe's federal plaza in Chicago, and Calder's Bent Propeller that was virtually destroyed in the plaza outside the World Trade Center on 9/11. And then there are his mobiles. The man invented the mobile. That means every nurseling for the last fifty years who has stared up at rotating, bobbing shapes above his crib has Calder to thank for the hours of entertainment. Sartre, in an essay on Calder, wrote that "a mobile is a little private celebration, an object defined by its movement and having no other existence. It is a flower that fades when it ceases to move, a 'pure play of movement' in the sense that we speak of a pure play of light."

Nothing I could write about Calder could justify the reverence I have for his artistic work; growing up I learned quickly to associate his name with those vibrant stabiles that bring so much life to public plazas, particularly La Grande Vitesse in the Grand Rapids, Michigan plaza that bears Calder's name, as well as the giant red Flamingo stabile that sits within Mies van der Rohe's federal plaza in Chicago, and Calder's Bent Propeller that was virtually destroyed in the plaza outside the World Trade Center on 9/11. And then there are his mobiles. The man invented the mobile. That means every nurseling for the last fifty years who has stared up at rotating, bobbing shapes above his crib has Calder to thank for the hours of entertainment. Sartre, in an essay on Calder, wrote that "a mobile is a little private celebration, an object defined by its movement and having no other existence. It is a flower that fades when it ceases to move, a 'pure play of movement' in the sense that we speak of a pure play of light."

Only recently did I learn that Calder began his artistic career by designing toys. In 1927 he designed a series of kinetic toys for the Gould Manufacturing Company of Oshkosh, Wisconsin that in their design bear witness to Calder's mechanical and artistic genius. Most of the toys are pulled by a string, and lurch along in various movements that mimic the movements of the creatures they were designed to represent: a frog, a seal, a skating bear, a kangaroo, a cow, a shark. Calder designed them to be pulled on axles that connected the wheels not at their center but at what are called "eccentric" points. Thus, the frog and the kangaroo hop. The duck bobs like real ducks do. And the shark lurches on its wheels, allowing its tail to shift back and forth like a fish navigating currents. Before embarking on his toymaking career, Calder graduated from the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey, with a degree in mechanical engineering. One can't help but speculate that this early application of engineering principles to a few deceptively simple toys ultimately led to his intricately balanced and wonderfully playful mobiles.

Only recently did I learn that Calder began his artistic career by designing toys. In 1927 he designed a series of kinetic toys for the Gould Manufacturing Company of Oshkosh, Wisconsin that in their design bear witness to Calder's mechanical and artistic genius. Most of the toys are pulled by a string, and lurch along in various movements that mimic the movements of the creatures they were designed to represent: a frog, a seal, a skating bear, a kangaroo, a cow, a shark. Calder designed them to be pulled on axles that connected the wheels not at their center but at what are called "eccentric" points. Thus, the frog and the kangaroo hop. The duck bobs like real ducks do. And the shark lurches on its wheels, allowing its tail to shift back and forth like a fish navigating currents. Before embarking on his toymaking career, Calder graduated from the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey, with a degree in mechanical engineering. One can't help but speculate that this early application of engineering principles to a few deceptively simple toys ultimately led to his intricately balanced and wonderfully playful mobiles. But there is a clear transition, and it is wonderful to behold: Calder's experimenting with various toy designs led to the development of a complex miniature circus in his studio. Calder had long been fascinated by the circus, and in his twenties he paid his way through art classes by selling a number of illustrations of the Barnum and Bailey's Circus to the National Police Gazette. In the late 1920s, Calder developed his own one-man circus, with tiny performers made of "cork, wire, wood, yarn, paper, string, and cloth," carefully engineered to walk tightropes, dance, tame lions, lift weights, and engage in gymnastics and acrobatics in and above the ring. Acting as omniscient ringmaster, Calder would manipulate the wire performers while his wife wound circus music on the gramophone in the background. While struggling as a more traditional artist in Paris, Calder began two-hour improvised performances of his Cirque Calder that recreated the performance of an actual circus. The show soon became a popular diversion among the Parisian avant-garde, and Calder began charging an entrance fee to see the big-top circus that could be packed into a suitcase. I like to imagine Calder's rented Montmartre studio on some smoky conglomerated pre-War Parisian night, filled with the likes of Jean Cocteau, Picasso, Joan Miro, James Joyce, Fernand Leger, Le Corbusier, Thomas Wolfe, and Andre Kertesz watching the young American perform his wire circus.

But there is a clear transition, and it is wonderful to behold: Calder's experimenting with various toy designs led to the development of a complex miniature circus in his studio. Calder had long been fascinated by the circus, and in his twenties he paid his way through art classes by selling a number of illustrations of the Barnum and Bailey's Circus to the National Police Gazette. In the late 1920s, Calder developed his own one-man circus, with tiny performers made of "cork, wire, wood, yarn, paper, string, and cloth," carefully engineered to walk tightropes, dance, tame lions, lift weights, and engage in gymnastics and acrobatics in and above the ring. Acting as omniscient ringmaster, Calder would manipulate the wire performers while his wife wound circus music on the gramophone in the background. While struggling as a more traditional artist in Paris, Calder began two-hour improvised performances of his Cirque Calder that recreated the performance of an actual circus. The show soon became a popular diversion among the Parisian avant-garde, and Calder began charging an entrance fee to see the big-top circus that could be packed into a suitcase. I like to imagine Calder's rented Montmartre studio on some smoky conglomerated pre-War Parisian night, filled with the likes of Jean Cocteau, Picasso, Joan Miro, James Joyce, Fernand Leger, Le Corbusier, Thomas Wolfe, and Andre Kertesz watching the young American perform his wire circus.

As his reputation among the avant-garde grew, Dutch painter Piet Mondrian invited Calder to his studio, and it was there, in viewing a white wall with cardboard rectangles of varying colors tacked on it, that he was inspired to delve into the abstract. He felt the rectangles could be made "to oscillate in different directions, and at different amplitudes." The visit proved to be the "shock that started things," he said later. Within a few months he was making mobiles.

I was writing with greg from daddytypes last week about the Calder toys and Cirque Calder and he mentioned how much he loved Carlos Vilardebo's 1961 film of Calder performing his circus, and I remembered I had it on DVD somewhere in my collection of bootlegs, so I ripped it, converted it, and uploaded it to youtube in four-minute chunks. The video quality on my version was never great, so it's perfect for youtube. It is a remarkable film, not just for the ingenuity of its subject but for the gravity of seeing one of the true geniuses of the 20th century playing circus just like he did when he was an unknown young man:

That's part one. Here's part two; Part three; and Part four. It's a total of 18 minutes or so. My favorite part is when the lion shits and he covers it with sawdust.

Several Calder toys are still being manufactured and are for sale on the internet, including his elephant and cat puzzles, the kangaroo, the bull push toy, and, of course, the shark Juniper is playing with in the picture above. Those are expensive as hell, display pieces more than toys, really. But they are all the evidence I need that a well-engineered toy doesn't have to have microchips in it to be remarkable.

Friday Morning Street Urchin Blogging

Posted by jdg | Friday, June 16, 2006 | Friday Morning Street Urchin Blogging

I am back from my whirlwind tour of Detroit; it turns out the owner of the place we'd already bid on thinks she's still living in 2003 with its 4% interest rates and its millions of rabid investors watching late-night get-rich-quick infomercials telling them to take out second mortgages on their little ranch homes to buy more and more REAL ESTATE. That meant I had to get on a plane to look at other properties on the market. I'm beginning to think that some real estate agents are like lawyers, but lie twice as much (meaning they never tell the truth).

I am back from my whirlwind tour of Detroit; it turns out the owner of the place we'd already bid on thinks she's still living in 2003 with its 4% interest rates and its millions of rabid investors watching late-night get-rich-quick infomercials telling them to take out second mortgages on their little ranch homes to buy more and more REAL ESTATE. That meant I had to get on a plane to look at other properties on the market. I'm beginning to think that some real estate agents are like lawyers, but lie twice as much (meaning they never tell the truth).

After Wood fed me four beers and dropped me off at the airport for the red-eye I stood and drunkenly watched people getting on and off planes with their babies, relieved that I did not need to entertain a 16-month old for the entirety of a 2300 mile flight while simultaneously missing my little girl so much and feeling like I could not bear those 36 hours apart from her. It became clear why airports have little toy stores next to the duty-free and magazine shops: to prey on our unending guilt.

I watched lovers' hands slip apart seconds before one turned a boarding pass and license over for inspection; I know that pain, I thought. In September 1996 I left Wood at Detroit Metro Airport, bound for Dublin, unsure of when I'd see her again. I made a fool of myself crying on that flight, back when they let non-passengers into the boarding areas and you could watch your loved ones disappear down jetways. We did it over and over but it never became easier. I thought of August, 2001, watching her leave SFO for Cambodia. Airports are such theaters of human misery, when any departure looms. It is easy to forget they are also the site of reunions.

I am scared of flying, of trusting all that metal and those two men who strip you of all control and temporarily take responsibility of your fate. I clutch a talisman at takeoff, a little toy Wood gave me before I first left for Ireland ten years ago. I pray. I realized on the flight to Detroit that I'm not scared of dying. I'm scared of having the last sound I hear be middle-aged women screaming.

After I looked at 12 homes Monday morning, compulsively videotaping and photographing every room for Wood's benefit, I met up with Melissa Summers from Suburban Bliss and we walked around the Lafayette plaisance and I talked about Mies van der Rohe and we drove around Belle Isle looking at dozens of vintage, rusting playgrounds and an abandoned zoo and I talked about Frederick Law Olmstead and we looked at the Detroit skyline and I said what she said I said. I was afraid I was talking too much. Wood and I will be bringing a couple six packs of Bell's up to Royal Oak this fall, I think.

Detroit is beautiful in the summer. It just needs its lawn mowed. I have forgotten, it seems, how much more lush foliage is when you only get it for half the year. It's cliche but I do miss seasons. I miss having memories associated with the smell of autumn, with those first few days of any season where the change is so welcome you cannot bear to ignore it. I cannot live somewhere where change is tectonic. I walked through Greektown, to Woodward and then east again down Lafayette. No one killed me, but several people smiled pleasantly and said "hello." You'd have more luck squeezing champagne from soggy bok choi than getting that kind of friendliness from my neighbors in San Francisco.

My girls picked me up at the airport yesterday, and from far away I saw Juniper stretch her arms out to me with an awareness that she had not seen me for awhile, a sense that she had missed sitting in the crook of my arm and talking about lions and buses. And for the first time in ten years I got off a plane and ran towards someone other than Wood in the arrivals hall.

Upper playgrounds

Posted by jdg | Monday, June 12, 2006 | Design , Isamu Noguchi , Nogucji playgrounds , playscapes

Six months ago, we didn't have much use for playgrounds; if we came across one with infant swings, I might let Juniper slump and squeal through the air, but there wasn't much else she could do. Nowadays, our life revolves around playgrounds: if we go anywhere in the city, we must make sure there is a playground nearby or there will be hell to pay. We live near Golden Gate Park, the site of the nation's oldest public playground, built in 1887. When Juniper was four days old, we took her for her first walk in the park and ended up in the playground, watching the toddlers and older kids run around, and I looked at my four-day-old daughter and couldn't imagine how she could ever be old enough to play in any of the awesome vintage 70s equipment that filled the giant playground. Turns out she wouldn't be. Not so long ago, we took her there only to discover it was gone. A rental chain-link fence prevented entry, and through the fence you could see that all of the great old equipment had disappeared. The slides: gone. The swings: gone. The kick-ass hexagonal honeycomb space maze: gone.

We live near Golden Gate Park, the site of the nation's oldest public playground, built in 1887. When Juniper was four days old, we took her for her first walk in the park and ended up in the playground, watching the toddlers and older kids run around, and I looked at my four-day-old daughter and couldn't imagine how she could ever be old enough to play in any of the awesome vintage 70s equipment that filled the giant playground. Turns out she wouldn't be. Not so long ago, we took her there only to discover it was gone. A rental chain-link fence prevented entry, and through the fence you could see that all of the great old equipment had disappeared. The slides: gone. The swings: gone. The kick-ass hexagonal honeycomb space maze: gone.

I nearly shed a tear that day, knowing that we would no longer be living in San Francisco when the new playground would be completed, but also knowing that they would inevitably replace it with the sterile, formulaic, lawyer/insurance-company-approved plastic playground monstrosities that are ubiquitous on most playgrounds today.

In our informal survey of other San Francisco playgrounds, I have realized that, like dollhouses, playgrounds are almost universally void of good design. If it's not the uninspired, safe plastic structures that are little more than exersaucers on growth hormones, it's a typical clunky 80s wooden jungle gym. I did find an awesome 70sish playground in the Fillmore with this Calder-esque climbing structure and these vertical tubes. It struck me that playgrounds have so much untapped potential for great design. Innovation seems limited to adding things like 4-foot climbing walls and flashy moving parts that inevitably break. Is it possible for a playground to be functional, fun and beautiful?

I just finished reading a long-lost screenplay for Charlie Chaplin's tramp character written by James Agee in the 1940s. The film was never made (by the time Agee had written it, Chaplin felt he was too old to play the tramp) but it could have been. Reading the screenplay, you can't help but think, "damn this would have been an amazing film." This got me thinking about all the great creative acts that, for one reason or another, never came into being. To architects and designers, this must happen all the time, when unrealized projects and plans just can't be brought to reality for any number of reasons.

I did a bit of poking around, and learned that the great sculptor, designer, and landscape architect Isamu Noguchi created a number of unrealized playgrounds. They are an important, but little-considered part of his work, which Noguchi himself acknowledged as "the kernel out of which have grown all my ideas relating sculpture to the earth." Noguchi believed children's playgrounds should be "sculptural landscapes." Only one of his many playground designs was ever actually built in America, the Playscapes playground completed in 1976 at Piedmont Park, in Atlanta, Georgia. I have never been there, but if any readers have seen it or been there I'd love to hear their impressions. From the pictures I have seen, it looks really cool.

I did a bit of poking around, and learned that the great sculptor, designer, and landscape architect Isamu Noguchi created a number of unrealized playgrounds. They are an important, but little-considered part of his work, which Noguchi himself acknowledged as "the kernel out of which have grown all my ideas relating sculpture to the earth." Noguchi believed children's playgrounds should be "sculptural landscapes." Only one of his many playground designs was ever actually built in America, the Playscapes playground completed in 1976 at Piedmont Park, in Atlanta, Georgia. I have never been there, but if any readers have seen it or been there I'd love to hear their impressions. From the pictures I have seen, it looks really cool.

The first playground Noguchi was commissioned to design was a "play mountain" in New York City, which was rejected in 1933 by the powerful New York City Parks Commissioner Robert Moses, a dude who apparently hated modern art even more than my dad. For nearly 30 years, Moses thwarted Noguchi's designs for several New York City playgrounds. His model for a swingset with multiple lengths of swing was originally designed for an unrealized Hawaiian playground, but was met with harsh criticism for its potential danger when he proposed it for another New York playground in 1939. The design has since been successfully incorporated into Noguchi playgrounds in Atlanta and Japan.

The first playground Noguchi was commissioned to design was a "play mountain" in New York City, which was rejected in 1933 by the powerful New York City Parks Commissioner Robert Moses, a dude who apparently hated modern art even more than my dad. For nearly 30 years, Moses thwarted Noguchi's designs for several New York City playgrounds. His model for a swingset with multiple lengths of swing was originally designed for an unrealized Hawaiian playground, but was met with harsh criticism for its potential danger when he proposed it for another New York playground in 1939. The design has since been successfully incorporated into Noguchi playgrounds in Atlanta and Japan. Conscious of the criticism that his modern geometric sculpture would cause injuries to children, Noguchi's next project was a more contoured, gentle landscape sculpture. Noguchi said it "would be proof against any serious accidents, being made of entirely earth modulations. Exercise was to be derived automatically in running up and down the curved surfaces. There were various areas of interest, for hiding, for sliding, for games." This playground was killed by NYC officials in 1941. Noguchi's next Manhattan project was a playground at the United Nations headquarters for the delegates' children. Noguchi took the project in 1952 because he thought Moses would not have jurisdiction to kill a project at the U.N. But Noguchi underestimated Moses, who called its design a "hillside rabbit warren" and made su

Conscious of the criticism that his modern geometric sculpture would cause injuries to children, Noguchi's next project was a more contoured, gentle landscape sculpture. Noguchi said it "would be proof against any serious accidents, being made of entirely earth modulations. Exercise was to be derived automatically in running up and down the curved surfaces. There were various areas of interest, for hiding, for sliding, for games." This playground was killed by NYC officials in 1941. Noguchi's next Manhattan project was a playground at the United Nations headquarters for the delegates' children. Noguchi took the project in 1952 because he thought Moses would not have jurisdiction to kill a project at the U.N. But Noguchi underestimated Moses, who called its design a "hillside rabbit warren" and made su re the playground would never get built by refusing to allow the city to erect a necessary protective fence on the East River-side of the playground. Noguchi described it as "A jungle gym transformed into an enormous basket that encourages the most complex ascents and all but obviates falls. In other words, the playground, instead of telling the child what to do (swing here, climb there) becomes a place for endless exploration, of endless opportunity for changing play. And it is a thing of beauty as the modern artist has found beauty in the modern world."

re the playground would never get built by refusing to allow the city to erect a necessary protective fence on the East River-side of the playground. Noguchi described it as "A jungle gym transformed into an enormous basket that encourages the most complex ascents and all but obviates falls. In other words, the playground, instead of telling the child what to do (swing here, climb there) becomes a place for endless exploration, of endless opportunity for changing play. And it is a thing of beauty as the modern artist has found beauty in the modern world." In 1961, Noguchi had a final opportunity to design a playground in New York City, this time for Riverside Park in collaboration with the architect Louis I. Kahn. After a long, drawn-out process of objections and re-designs, Noguchi's resolve and faith in his design and philosophy of playgrounds as "sculptural landscapes" was deepened. He said, "I later came to feel that children should not be restricted to fenced-in concrete play areas, and that some parks or parts of some parks, should become 'play gardens.'" But like the others, the Riverside Park project was killed by the bureaucrats.

In 1961, Noguchi had a final opportunity to design a playground in New York City, this time for Riverside Park in collaboration with the architect Louis I. Kahn. After a long, drawn-out process of objections and re-designs, Noguchi's resolve and faith in his design and philosophy of playgrounds as "sculptural landscapes" was deepened. He said, "I later came to feel that children should not be restricted to fenced-in concrete play areas, and that some parks or parts of some parks, should become 'play gardens.'" But like the others, the Riverside Park project was killed by the bureaucrats.

Several Noguchi playgrounds have been built in Japan (one in Sapporo, and one at the Kodomo no Kuni in Yokohama), and they show how Noguchi's sensibilities for landscape and play developed through the course of his frustrating New York experiences to create something truly wonderful. The play mountain and playground at Moerenuma Park, in particular, built on a reclaimed landfill, are really a complete testament to his full vision. These pictures show how wonderful playgrounds could be if we listened to rather than frustrate visionaries like Noguchi, who actually saw playgrounds as projects worthy of great design:

Friday Morning Street Urchin Blogging

Posted by jdg | Friday, June 09, 2006 | Friday Morning Street Urchin Blogging

"In every child who is born under no matter what circumstances and of no matter what parents, the potentiality of the human race is born again, and in him, too, once more, and each of us, our terrific responsibility toward human life: toward the utmost idea of goodness, of the horror of terrorism, and of God." ---James Agee, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men

"In every child who is born under no matter what circumstances and of no matter what parents, the potentiality of the human race is born again, and in him, too, once more, and each of us, our terrific responsibility toward human life: toward the utmost idea of goodness, of the horror of terrorism, and of God." ---James Agee, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men

During college in 1997 I lived on one side of a pink duplex across the street from a purported crackhouse owned by our local fundamentalist Christian state senator. My roommates were a Korean Dutchman and a guy who drove a VW bus that he'd hitchhiked to Florida to buy from two girls who'd spent the previous six years painting grateful dead lyrics and flowers on its beige exterior. On the day we moved in I found them tapping on the walls and moldings, "gonna hang a picture?" I asked. "People used to hide money in the walls of old houses," they said, leering at echoes like those old guys you see combing beaches with metal detectors.

When we moved in, the other side of the duplex was unoccupied, but soon a woman with five children rented the place. The oldest was ten or eleven, the youngest just a baby. I have no idea how old the rest of them were, just that they fit somewhere on that spectrum between the oldest and the youngest. They had the look of children sired by different fathers but intrinsically bound to each other by the genes of their mother, a straw-headed woman who had given each of them a similar head of scrubby blond hair. The oldest kid, a gangly girl of eleven, attended the same elementary school I once did, where we found crack pipes on the playground and played with them like toys. There was another straw-haired woman with them, the children's grandmother. She took care of the youngest ones while the mother worked.

One day not long after they moved in, my friend Koby from high school pulled up in his 1984 Datsun Sentra Hatchback. People called him Cold Cuts, because he really loved cold cuts, I guess. One thing I always admired about Koby and his family was that they never paid more than $200 for an automobile. They'd find somebody who needed to get rid of a 1983 Oldsmobile Ninety Eight station wagon and then they'd just drive that sonofabitch until they had to take the tags and the tape deck and leave it on the side of a highway somewhere. Koby told me that he'd heard about this farmer's field down in Indiana with a couple acres of mature marijuana plants and he wanted me to come with him. He had become much more dangerous since high school, and he was even more so when he had a treasure map. "You'll get shot," I said, and he just got pissed and drove off. A few hours later that night he pulled into our driveway and laid on the horn. We went out to see what all the commotion was about and there was Cold Cuts Koby with a shit-eating grin on his face. He popped the hatchback and under some Indian blankets were four or five garbage bags full of marijuana. Stalks of it. There had to be sixty or seventy pounds of dewy-wet plants in there, enough to get him sent to federal prison. He pulled off a few handfuls of buds and brought them inside our apartment. "Aren't you supposed to let those dry or something?" one of my roommates asked him, but he was too excited not to smoke his bountiful harvest immediately. He emptied out a Philly cigar casing (Koby refused to smoke anything but blunts) and I swear to god as he loaded it a cricket jumped out from among the buds. From that day forward my roommates referred to him as "Cricket-Weed Koby."

So Koby enjoyed his yield like a 19th-century shipping magnate with a Bolivar and a glass of Lagavulin Single Malt while clouds of wet brown campfire smoke filled our living room, and about five minutes later we heard a knock on our door.

It wasn't the cops: it was our neighbors. The mom. Or the grandma. Years of heavy smoking and hard living had made it impossible to tell. She had some sleepy-looking old guy behind her with a longneck in his hand and a cigarette tucked behind his ear. "What you guys smoking in there?" she asked coyly. My roommate feigned incomprehension. "Don't play with me boys, we can smell what you're smoking. Can we have some?" Koby was not one to suffer fools. I believe he got up in her face and used some hostile language unbefitting a gentleman of his stature, including, "fuck no"; "skanky-ass bitch"; "dirty-ass hoe"; and "white-trash-piece-of-shit motherfuckers."

We didn't hear from our neighbors for a couple of weeks after that, other than the dull screams and wails of the kids through the walls. One night we did get another knock on our door. This time it was grandma for sure, holding a lit cigarette and a nearly-empty bottle of vodka in one hand. She was holding her other hand up to her head and kind of moaning. "Do you boys have any aspirin?" she asked. "I just got a nail shoved up in my head." She removed her hand from her head, and true to her word, there was a small puncture wound with dried blood streaming down her forehead. One of us rushed to grab some bottles of aspirin and ibuprofin and I said, "You know, you should probably go to the hospital for that."

"Oh, I'll be alright," she said. "I just need some aspirin."

After she thanked us, my roommates and I just kind of sat around dumbstruck. How does one get a nail "shoved up in" one's head? What was going on on the other side of our walls?

Over the next few months of autumn, we really started to get to know the little kids, who were all starved for attention We shared a front porch, and whenever one of us sat out there reading or just watching co-eds walk down the sidewalk, the kids would get us to toss them up into the air or swing them around the front yard. One time a bunch of hippies made a gigantic vat of hummous and ate it on our front porch. The little kids joined in, a bunch of bearded guys breaking pita with a gangly troupe of towheaded porch urchins. They were always after our food. The porch was old and dilapidated and they treated it like a jungle gym (they had no other toys as far as I could tell). They were always getting hurt when wooden planks or beams broke or collapsed. We'd hear them scream and rush to see if they were okay. Nobody would emerge from their side of the duplex. The children were easily calmed as children who never get attention for their screaming often are. I did wonder, then, what it took to get them screaming as loud and as long as they did at night.

One of my roommates was the kind of guy who actually took his studying seriously, and he preferred doing it at our dining room table. With time, the screaming and constant noise of footsteps storming up and down the stairs next door and through the wall became too great a distraction, and he called to complain to the landlord, an ineffectual little twerp named "Dale" who washed his hands of any involvement. Over time the sounds we heard on the other side of the wall only grew more and more disturbing. A man had started living with them and his hoarse yells were more and more often the prologue to long bouts of screaming and more yelling. It all became very My name is Luka. I had long talks about what to do about it with the girl in the next house down who was getting her degree in social work. We thought about calling Child Protective Services.

By November they were gone. Dale had evicted them. They had only paid him $700, one month's rent. We came back from class one day and he was standing there on the porch wearing a dust-mask like an old Chinese lady and a big pair of rubber gloves carrying garbage bags full of clothes out of the house. He was very upset about the damage to his property. "They didn't even have any furniture in there," he said, disgusted. "Those kids were sleeping on piles of dirty old clothes, and everything smells like urine." We looked inside. The house, a mirror image of the one we inhabited on the other side of the wall, could not have been more different: there was no thrift store furniture; no empty bottles of Goldschlager decorating the mantle, no environmental science textbooks or Peruvian wall hangings. There were just piles of clothes, and stains on the carpet, and filth all over the walls.

The other side of the duplex sat empty for a month, and Dale came to us, desperate to learn if we knew of anyone who needed a place. "I don't want to rent it out to anyone like that again," he said. At that time Wood and her two friends were looking to move, and he offered us a finder's fee and gave them a huge discount on rent if they agreed to paint the walls and clean the place up themselves. I wanted so badly to live on the other side of the wall from Wood, I helped them paint the walls white. I will never forget what that side of the house looked like, or how it smelled, and how easily it was all cleaned up. When we were done, Wood and I sat on the porch, kicking at a broken plank still nailed to the porch.

I told her how I remembered kids in elementary school who were there one day and gone the next. I remembered the kids who really smelled, the kids whose outrageous behavior problems shocked the class and prevented the teachers from ever really teaching us anything. I had never seen how those kids lived. They had not been my friends. Their parents were not acquainted with my own.

What will happen to those kids who lived on the other side of the wall, we wondered. Where did they go?

Oh please don't go we'll eat you up we love you so!

Posted by jdg | Monday, June 05, 2006 | Where the Wild Things Are

We have entered the time in a toddler's life when she becomes mildly obsessive about particular things beyond the immediate attraction of her mother's nipples, or, as my wife so eloquently put it yesterday in Piagetian terms : "object permanence is a bitch."

We have entered the time in a toddler's life when she becomes mildly obsessive about particular things beyond the immediate attraction of her mother's nipples, or, as my wife so eloquently put it yesterday in Piagetian terms : "object permanence is a bitch."

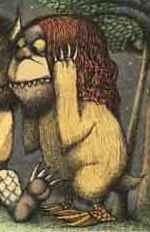

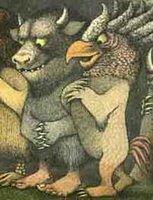

Right now I'd say the primary object of her obsession is Maurice Sendak's Where the Wild Things Are, or in Juniperian terms, "Ah-ooh, Ah-ooh, Ah-ooh!" (the sound the wild things make during the wild rumpus). Given her nightly reading demands, it is the last thing she thinks about before she retires. And considering the incessant chanting of ah-ooh, ah-ooh, ah-ooh we hear from her crib at 5:45 in the morning, it is probably the first thing she thinks about when starting her day. When we are out and about and see anything anywhere that resembles a wild thing, the chanting starts anew. She carries the book around during the day, thumbs through it, chanting and waving bye bye to the wild things. I have read it so many times I have begun to create subplots in my head and imagine subtexts and backstories and sequels just to keep me from starting a wild rumpus between my head and the fucking bookshelf.

My favorite wild thing is this one. I know Sendak wrote the book in 1963, a full year before the Beatles would invade and encourage every buzz-cut American male to grow their hair out nice and shaggy, so check out Wild Thing #3 here. Like Agee or Kerouac before him, this dude is clearly ahead of his time. Look at that red hair! He looks like he could have been a backup keyboard player for Rush in 1974. What I love best about Wild Thing #3's hair is that he clearly styles it. Wild Thing #3 may be wild, but not so wild that he can't occasionally wash, condition, rinse, repeat, and then conair the shit out of his hair before brushing it more times than Mary Ingalls. Although I must say, it does look a little greasy during Max's visit.

My favorite wild thing is this one. I know Sendak wrote the book in 1963, a full year before the Beatles would invade and encourage every buzz-cut American male to grow their hair out nice and shaggy, so check out Wild Thing #3 here. Like Agee or Kerouac before him, this dude is clearly ahead of his time. Look at that red hair! He looks like he could have been a backup keyboard player for Rush in 1974. What I love best about Wild Thing #3's hair is that he clearly styles it. Wild Thing #3 may be wild, but not so wild that he can't occasionally wash, condition, rinse, repeat, and then conair the shit out of his hair before brushing it more times than Mary Ingalls. Although I must say, it does look a little greasy during Max's visit.

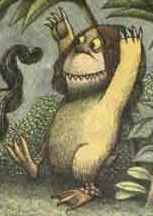

Wood's favorite is Wild Thing #1, the one on the cover. Why? Because he has human feet, of course. I find him a bit boorish.

Wood's favorite is Wild Thing #1, the one on the cover. Why? Because he has human feet, of course. I find him a bit boorish.I do like that he is such good pals with that rooster-headed Wild Thing. The look they're giving each other during the second page of the wild rumpus tells me there just may be something between those two. I don't really like the rooster-headed Wild Thing. He seems to be all cock-n-strut with no substance; he seems somewhat vapid, with none of the soulfulness you see in the other Wild Things' eyes. I sense a broken heart in Wild Thing #1's future.

All of my imagining may be cured however, as all imagination is cured: through the wonder of motion pictures. Yes, it's true, Maurice Sendak has cashed his check and sold the rights for Where the Wild Things Are to become a movie. Production begins this month on a film version that (as with all less-than-500 word children's books that become potential blockbusters) will stretch a simple story into two hours of CGI-saturated delight. It should be released in 2008, just in time for Juniper to become obsessed with the movie and demand to watch it over and over and over.

But before we get all hopeful that this movie will be as awesome as Garfield Two: A Tale of Two Kitties, we should consider who is at the helm: Where the Wild Things Are is being directed by Spike Jonze (who directed all those movies I couldn't understand) and the screenplay is being written by Dave Eggers, who is apparently some guy who runs a pirate supply store in San Francisco. The film version will include the voice of Benicio Del Toro as a Wild Thing and Catherine Keener as Max's mom. Hello, Hollywood: what the fuck? Dave Eggers? Couldn't they have just gotten the guy who adapted Cat in the Hat? And were Rosie O'Donnell and Robin Williams too busy this summer to share with us the gift of hilarity? Cripes, this is going to horrible.

At least there has been one good movie made about Wild Things: